In this education article, we hit the road on a ride-along with TAG Heuer! Together, we delve into the rich (and sometimes turbulent) history of the chronograph, how it works, and what types of chronographs are out there.

In recent years, many watch brands have stepped up to the plate when it came to amping up their artistic and technical abilities. TAG Heuer is but one of those brands, whose releases as of late have consistently stolen the limelight of the watch world. Of course, there are many factors as to why this is so – a topic for another time, perhaps – but one major component would be their mastery over one of horology’s most coveted complications: the chronograph.

Everybody knows what a chronograph looks like, but what does it do? Who made the first one? And is it bad to leave your chronograph running? All of that and more will be answered if you read on. Start your engines!

History of the Chronograph

Before we can talk about the chronograph, however, we have to talk about those responsible for its conception and popularity. While the chronograph is popularly associated with the racing world, its origins lay in the stars: French watchmaker Louis Moinet invented the chronograph in 1816, which was used alongside astronomical equipment to time cosmic phenomena.

The Compteur de Tierces, as he called it, was shockingly ahead of its time, beating at an unbelievable 30Hz (216,000bph). This is far beyond the modern luxury standard of 4Hz (28,800bph) and yet laid the groundwork for the chronograph as we know it today.

The first time the chronograph would be used in a racing context was thanks to one Nicolas Matthieu Rieussec. He made the first commercially viable chronograph in 1821 to help King Louis XVII time horse races at the Champs de Mars, which began the establishment of the chronograph as a sport and racing icon.

In 1860, one Edouard Heuer threw his hat into the watchmaking ring, and would eventually patent two inventions that would become the backbone of his company for years to come: his first chronograph in 1882 and the oscillating pinion in 1887, the latter becoming a staple of all chronographs made even to this day. From there, Heuer’s legacy, TAG Heuer’s legacy, and the legacy of the chronograph only grew.

At the turn of the 20th Century, Heuer flourished, marked by milestones like their partnership with the Olympic Games in 1920, establishing their legacy as the standard timekeeper for sports thereafter. The Autavia name would follow in 1933, as would other iconic models like the Abercrombie & Fitch Seafarer. Heuer even went to space in 1962, where astronaut John Glenn wore a Heuer stopwatch mounted to his suit!

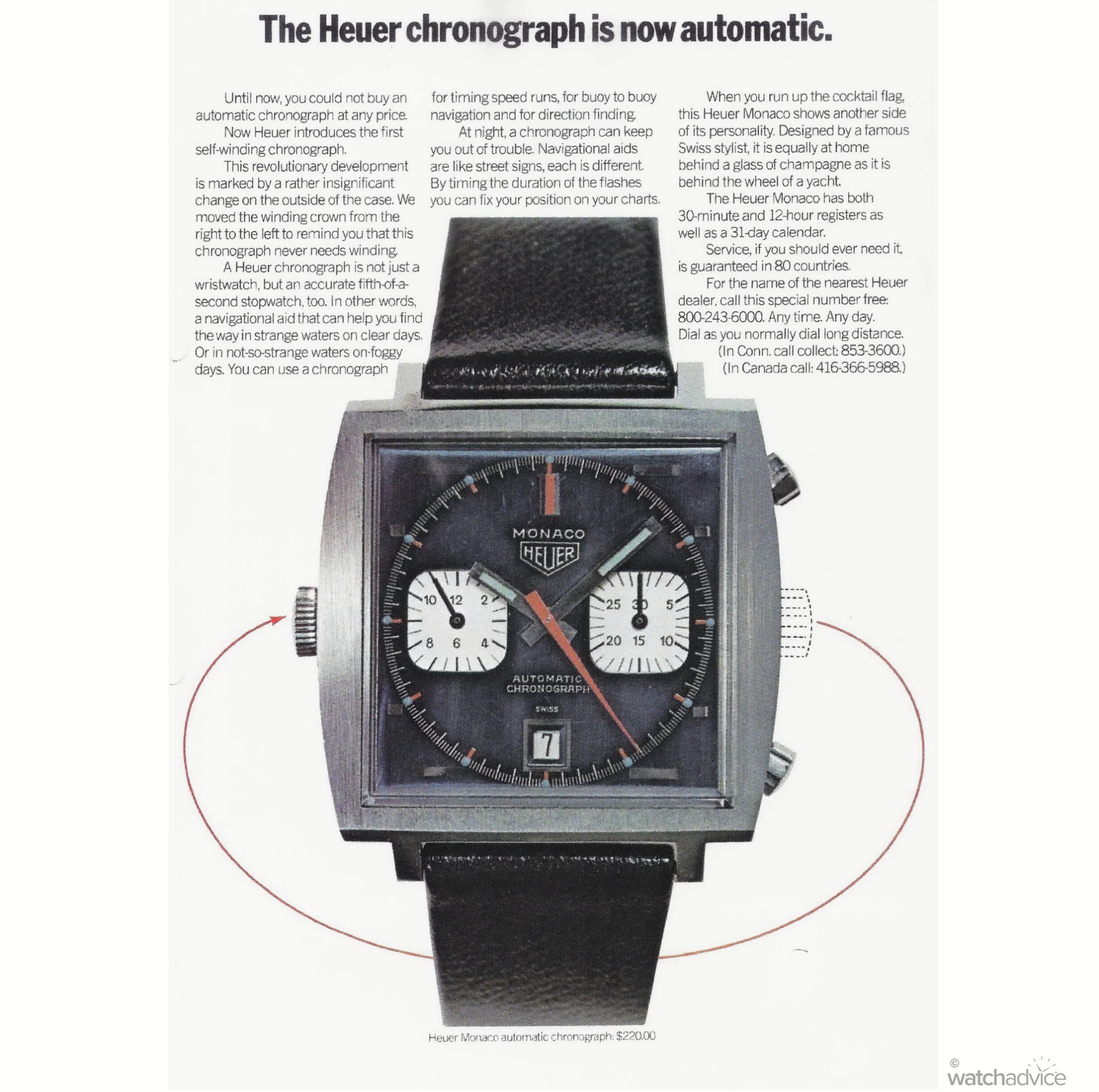

It wasn’t until the sixties that Heuer’s reputation in chronograph manufacturing would skyrocket. Jack Heuer, the grandson of Edouard, not only invented the now-recognisable Carrera lineup but also participated in ‘Project 99’ alongside teammates in Breitling, Hamilton-Büren, Leonidas and Dubois-Dépraz. The result was the Calibre 11 – the world’s first automatic chronograph – which debuted alongside the legendary Heuer Monaco.

Before anyone gets too worked up, I recognise that Zenith had the first automatic chronograph movement – the El Primero – in 1965. However, Heuer was the first to globally release the Calibre 11 with the debut of the Monaco. It’s like saying Russia could have gone to the moon before the United States did but decided not to because it was their day off.

How Does It Work?

Without getting too deep into technological jargon, the operation is quite simple. Every chronograph watch has three functions: Starting, stopping, and resetting. These are typically run through the use of two buttons, commonly referred to as ‘pushers.’ The top pusher is normally used for starting and stopping the chronograph’s second hand, and the bottom pusher resets the hand to zero. In rare instances, you may find a chronograph’s features run by a single or ‘mono’ pusher.

Nevertheless, every chronograph works similarly behind the scenes – the start/stop pusher connects and disconnects the complication with the general timekeeping mechanism, moving it vertically or horizontally. The tech behind this movement is typically known as the ‘clutch,’ with the connection managed by either a heart-shaped cam and lever system or a chess rook-shaped column wheel.

For TAG Heuer, their premium Heuer 02/TH 20-00 movement uses a vertical clutch managed by a column wheel. This is particularly advantageous on two fronts:

- Firstly, a vertical clutch works allows the chronograph mechanism to be directly driven by the mainspring, allowing for reduced wear and tear, and

- A column wheel allows for a smoother engagement of the chronograph mechanism, reducing the likelihood of the chronograph’s second hand stuttering.

Of course, the oscillating pinion is present in the Heuer 02/TH20-00, as it has been for almost every chronograph movement since Edouard Heuer invented it.

Chronographs are also typically accompanied by a series of registers or ‘sub-dials’ that assist in timekeeping. In TAG Heuer, these consist of a 30-minute register and a 12-hour register, alongside a small seconds complication for accurate time-setting. From supercars to steaks, there’s nothing that it can’t tackle, allowing you to time virtually everything.

However, I’ve noticed quite a few people who aren’t timing anything, yet their chronographs are still on. Why is that? From what I’ve gathered, some people don’t think the watch is functioning due to the static second hand. Don’t worry, though, as the aforementioned small seconds complication is present on most modern TAG Heuers. If that’s moving, I can assure you that the watch is perfectly functional.

If you want to keep the chronograph running, however, it’s a mixed bag out there: Some say that running the watch ‘helps the oil on the gears spread more evenly,’ whilst others say that it enacts unnecessary wear-and-tear on the watch. I’m erring on the latter’s side, as it both wears down your gears and your watch’s power reserve – operating the chronograph takes more juice than normal. So, if you want to get all 80 hours out of your Heuer 02/TH20-00, don’t keep the chronograph running. Or do – I’m not going to tell you how to run your watch!

Modern-Day Chronographs

There are three standard types of mechanical chronograph: Simple, flyback, and rattrapante (split-seconds). Fortunately, TAG Heuer is in the business of manufacturing all three, which allows me to take you through what you would typically find for each.

Simple: TAG Heuer Carrera

The Carrera is TAG Heuer’s best example of a simple chronograph. Coming in many different sizes and flavours, it’s the essence of what a chronograph is and should be. This 39mm Carrera Glassbox is exactly what you would expect from a traditional chronograph offering, with two chronograph registers (often referred to as ‘bi-compax’) and a small seconds complication at the 6 o’clock.

Along the periphery of the dial runs a black-and-white tachymeter scale, which is a chronograph feature used to calculate speed based on time over a set distance. It’s a bit mind-bending at first, but The Edge Magazine from TAG Heuer puts it best:

- Start your chronograph when a moving object, like a car, passes a starting point.

- Stop the chronograph when the object travels a predetermined distance (for example, one mile or one kilometre).

- The seconds hand will point to a number on the tachymeter scale. This number represents the object’s speed in units per hour (like miles per hour).

If you start timing a car as it passes you and stop the timer when it has travelled one mile, and it took 30 seconds, the seconds hand will point to 120 on the tachymeter scale. This indicates that the car was moving at 120 mph. It looks complicated but it’s really that simple.

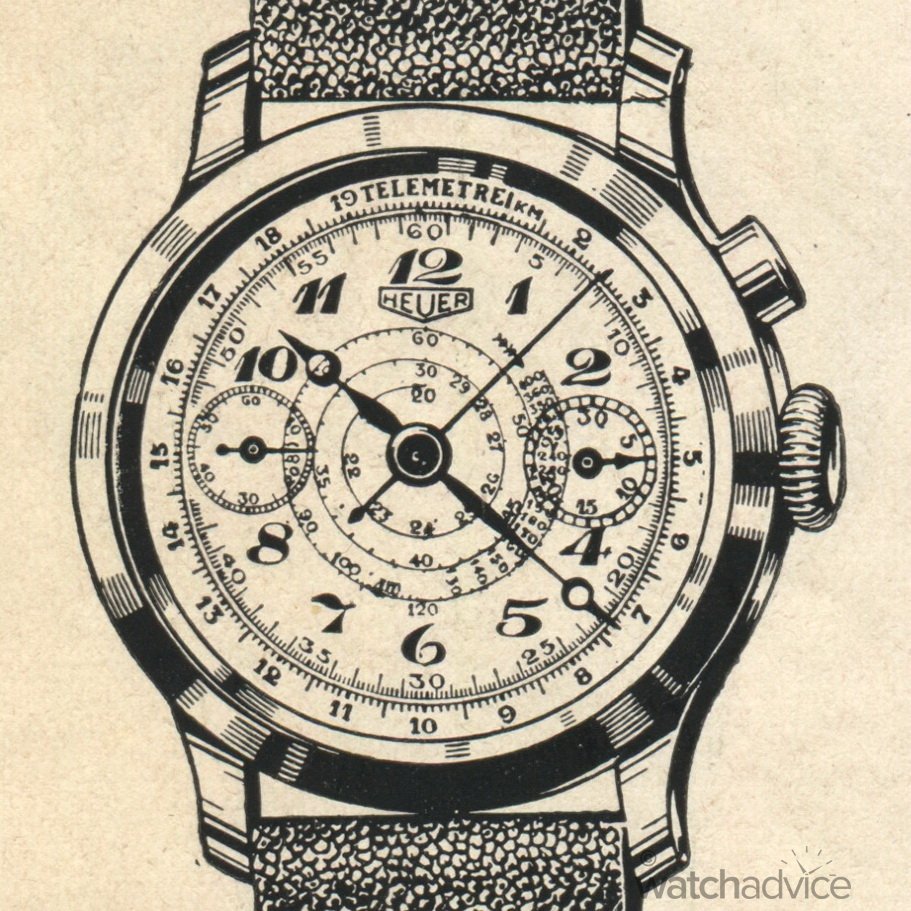

The Carrera models have also been known to come with another scale called a telemeter, such as this Calibre 18 Carrera (pictured above) from 2015. In this case, a telemeter is used for measuring the distance from an audible event. For example, if you see a storm and want to know how close it is, start the chronograph as soon as you see lightning and stop it as soon as you hear thunder. Whatever periphery number the second hand is pointing to indicates the distance you are from the storm. If you live in a tropical environment often hit by storms, this is a godsend, as you’ll know exactly how much time you may have to batten down the hatches.

Flyback: TAG Heuer Autavia

The Autavia is a great example of a flyback chronograph offering from TAG Heuer. Don’t believe me? You should check out our Hands On Review of it here and see for yourself!

In normal operation, A simple chronograph movement has to be stopped to be reset. But if you hit the reset button on a flyback chronograph, even when it’s still in use, all the timing hands get reset to zero and keep going. This is useful for recording dynamic events such as lap times and was historically used for navigation purposes by aviators to keep their flight paths on track. If you want to mess around with a flyback chronograph yourself, you should check out the TAG Heuer website as it has a fully interactive version of the Autavia. If you hit the reset pusher too many times, though, you may break the interactive model. (I’m not saying you should, but you can if you want to…)

From the surface, it’s not too different from the Carrera. Yes, it’s got that heritage-inspired style, and it’s still powered by the Heuer 02/TH 20-00. In this instance, however, it’s the Heuer 02F/TH 20-12, indicating its flyback function.

Another great example of a flyback chronograph is the TAG Heuer Monza. It operates similarly to the Autavia but is particularly interesting as it sports both a tachymeter and a pulsometer. You can use the pulsometer to check your heart rate by:

- Putting your hand over your heart or wherever you can feel your pulse

- Starting the chronograph and counting your pulses

- Once your pulse count hits 15, stop the chronograph and check where the second hand is pointing

It’s also useful if you need to check someone else’s pulse in an emergency. Of course, leave the medical stuff up to the professionals, but if you own a chronograph with a pulsometer, helping save a life with it will leave you with one heck of a story!

Rattrapante: TAG Heuer Monaco Split-Seconds

More recent to the roster is TAG Heuer’s triumphant return to creating rattrapante/split-second timepieces. Rattrapante, meaning ‘catch-up,’ is indicative of the watch’s main feature: Two chronograph hands. Used primarily to time events that end separately, the rattrapante usually involves the presence of a third pusher, which when pressed will stop one of the chronograph hands whilst the other one carries on. Pressing this pusher again will cause the stopped hand to catch up to the other one, continuing simultaneously as if nothing ever happened.

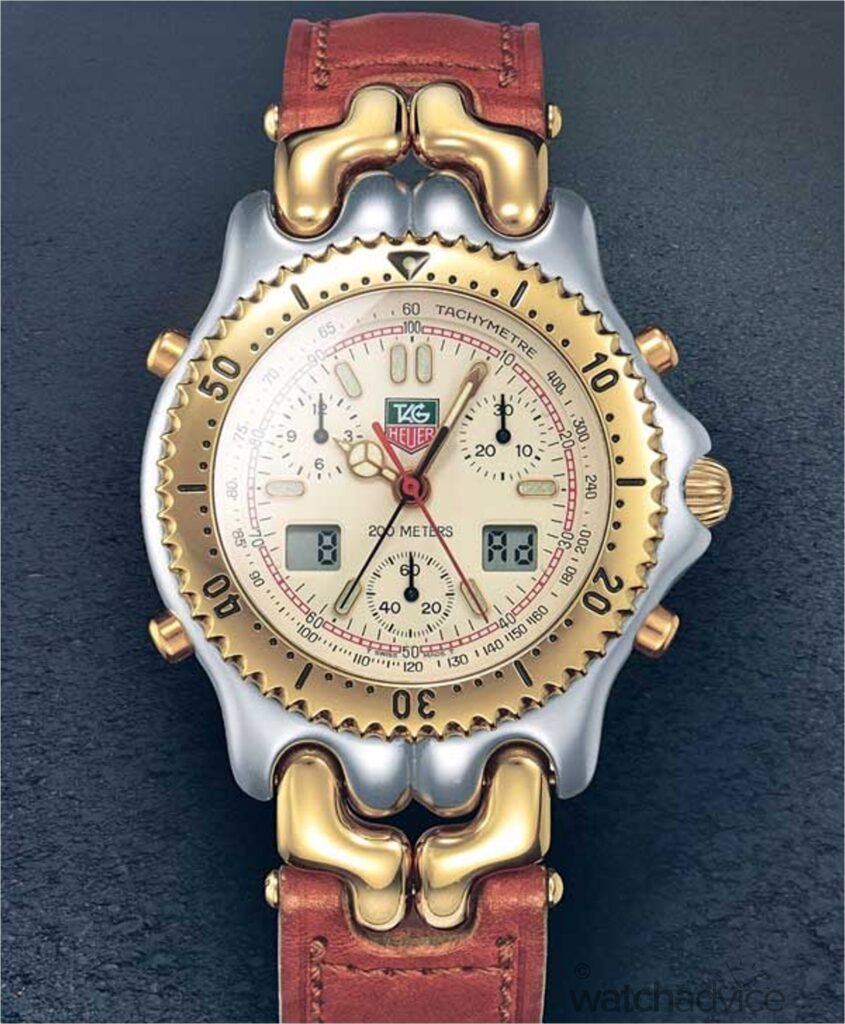

TAG Heuer is no stranger to making split-second watches – see the above, where Ayrton Senna wears his S/EL Ref. S25.706C – but they had only ever made them in quartz. Following their OnlyWatch donation, TAG Heuer decided to make a mechanical version for standard production in a new rendition of the Monaco

The rattrapante movement, titled TH 81-00, represents a massive step in TAG Heuer’s haute horlogerie journey. Sure, AUD$200,000 is a massive ask, as it’s a price point not commonplace for TAG Heuer watches, but it indicates to us and the rest of the watch world that their journey has only just begun.

Final Thoughts

Note that there is still so much to discover about the history of the chronograph and all the brands over the years that have pursued the ‘perfect chronograph.’ I’m sure that there was so much stuff I glossed over, but perhaps I’ll save those stories for another time.

In any case, TAG Heuer is a remarkable lens from which to view the evolution of horology’s most sought-after complication, from where it was in the past to what it is today. This is apparent simply through the variety of chronographs they created throughout their 164-year history, including the four I’ve just mentioned. If you’re interested in the full history of TAG Heuer, check it out at their website here!

As for the mono-pusher chronograph, TAG Heuer has yet to make one of those. Unless, of course, they were to dig into the archives and remaster the Ref. 2403 – and they’re kind of on a roll right now with heritage-inspired releases…