We take a look at the real cost of watch-making, and delve into why luxury watches are not as cheap to make as you think…

What’s the real cost of producing a luxury watch? It’s a good question, and one I’ve been wanting to tackle for a while. If you’ve been on the online forums, in different watch groups and even read the comments on social media posts from Watch Media, Influencers and the brands alike, you’ll often see comments like this: “It can’t cost more than a few thousand dollars to make that watch, and they charge how much!?” or “$20k for a watch that costs no more than $2k to make is ridiculous!”. Basically, something to that effect indicating that the profit margin in watches is massive. You also see comments like “It’s all marketing costs that drive the high prices” which I do have to laugh at as in many cases, the cost to market a brand isn’t all that much in comparison to all other business overheads. If a brand spends 10-15% of its overall cost base on marketing, they’re doing well.

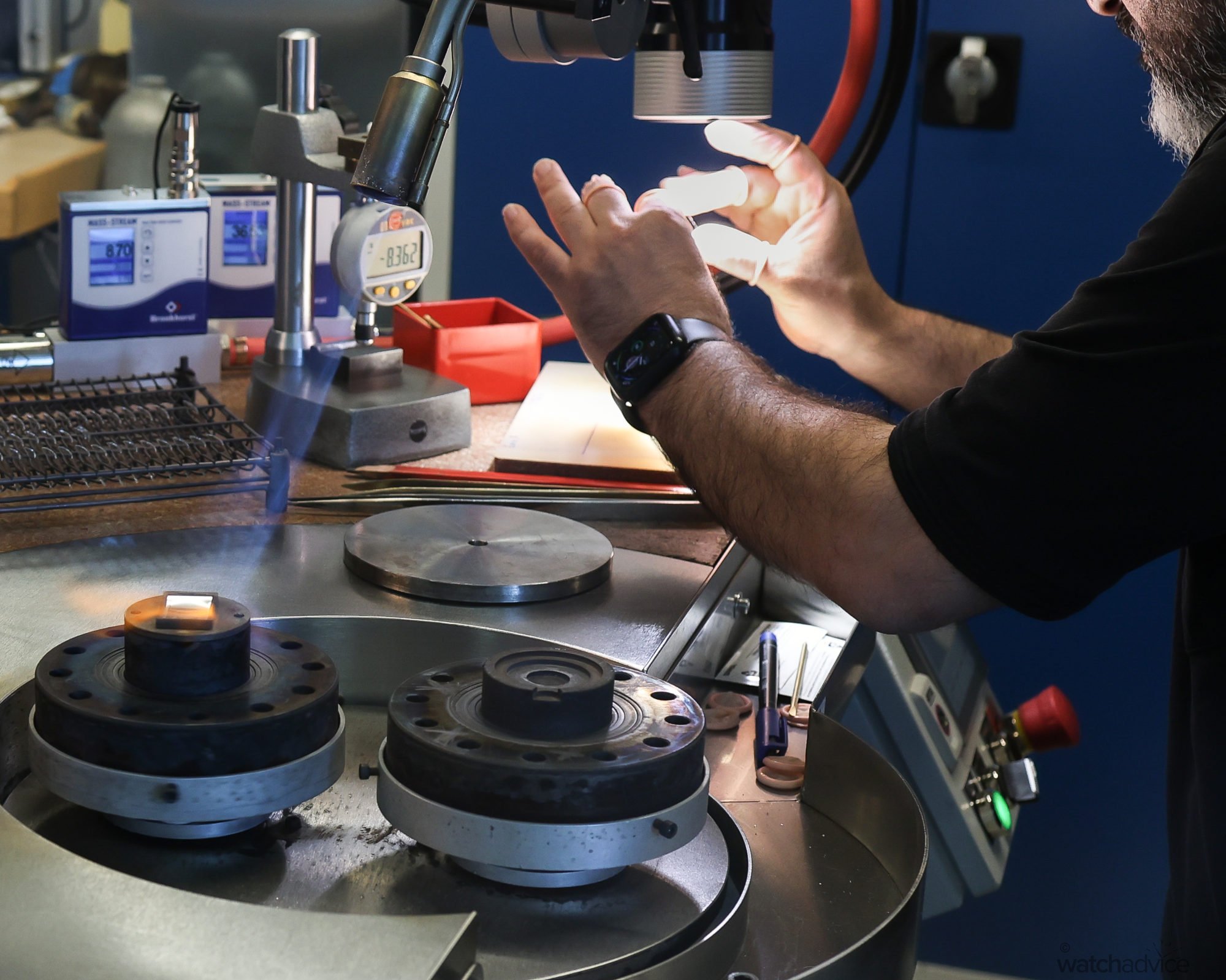

So these comments got me thinking, and also having recently done several Manufacture visits whilst in Switzerland and getting a first-hand look at the processes, machines, technology, labour force, overheads etc, I wanted to delve into the topic further. How much does it cost to produce watches? And are the profit margins really that big or are they smaller than many people out there believe?

Like with any business, the raw material cost to produce a product is really only a fraction of what it costs to make that product and get it to market and into customers’ hands. This goes for almost all businesses across all industries, not just the luxury watch world. If you sell shoes, what you buy them for, or the costs for you to make from raw materials is not what you sell them for. If it was, your business would be bankrupt in a matter of months. Add to this if you’re the supplier to a retailer, then you need to have a margin on your end, and the retailer on theirs. Use a distribution company? Then that’s another cut of the revenue that occurs between you, the distribution company and the retailer. You get the picture.

The other thing that many people don’t seem to take into account is the actual cost of running the entire business. This will obviously differ based on the business set-up, efficiencies, size of the business, distribution channels etc, but on the whole, the average Swiss watch brand (or any for that matter) will have similar types of overheads such as wages, insurance, electricity, water, IT infrastructure, manufacturing equipment, R&D costs, staff training, raw materials, taxes, building overheads, maintenance, freight and logistics, import and export costs, duties, supplier costs, marketing and advertising, plus trade show expenses. The list goes on. And if you have a network of boutiques, then you effectively have all this again (with the exception of R&D and a couple of others) but on a local level in each country for the boutiques and the staff in them. Just think of how much retail space is alone for a boutique in any major city where the luxury shopping is, such as the Champs Elysée in Paris, 5th Avenue in New York, Rodeo Drive in LA, or downtown Sydney or Melbourne. That is just one small part of the business operations.

So all of a sudden, the cost of running the business has to be amortised into each watch, and adjusted for the individual piece based on the materials used, the complexity of it, and the number of human hours that is needed to make and assemble the watch. Remember, most luxury watch brands may get their components made in machines, but they are more often than not finished and then assembled by hand – which takes time and effort.

All this is factored into the final price based on the margin needed to run a successful and profitable business. If not, then what’s the point? I certainly wouldn’t run a business that wasn’t profitable (unless it’s a charity) and if you have shareholders like many of the larger watch corporations such as Richemont, LVMH, and Swatch Group has, not making a profit is not an option as those shareholders then expect dividends and share price increases year after year.

Another element to take into account is the research and development of both movements and materials. New movements take time to research, design, develop and then test with prototypes. On the other hand, new materials for those brands that play in that space similarly take a long time to create and perfect. As the saying goes, time is money. When a brand takes 2-3 years to develop a new movement or case material, these costs need to be absorbed into the business today. The revenue then comes once the watch is released, and inevitably, much of this goes back into the business to support the costs at that point – and the cycle continues.

The other element that I wanted to touch on which does affect margins and profit is exchange rates. The luxury watch industry is an international industry which means that in the case of say Swiss watchmakers, they export all over the world from Switzerland and set pricing according to the regions that operate in. The regional pricing is done in a way so a watch here in Australia will cost roughly (not exactly, however) what it does comparatively in other markets and then adjusted to take into account the market, competition, import duties etc etc. Exchange rates impact all of this. In one example, the operating results of a major brand should have been in the plus single-digit growth, but due to unfavourable exchange rates and international volatility, was down to the tune of minus double digits. This is then absorbed into your overall cost base, and thus each watch effectively.

But enough of me rambling on about business costs and shareholders. All this is well and good, but I wanted to look at real-world examples from major watch brands. For this article, I won’t mention the brands at all as it’s not about singling out any specific company positively or negatively, but more commentary on the overall industry. As all the numbers are on the public record from company reports and industry publications, no industry secrets are being given away here either.

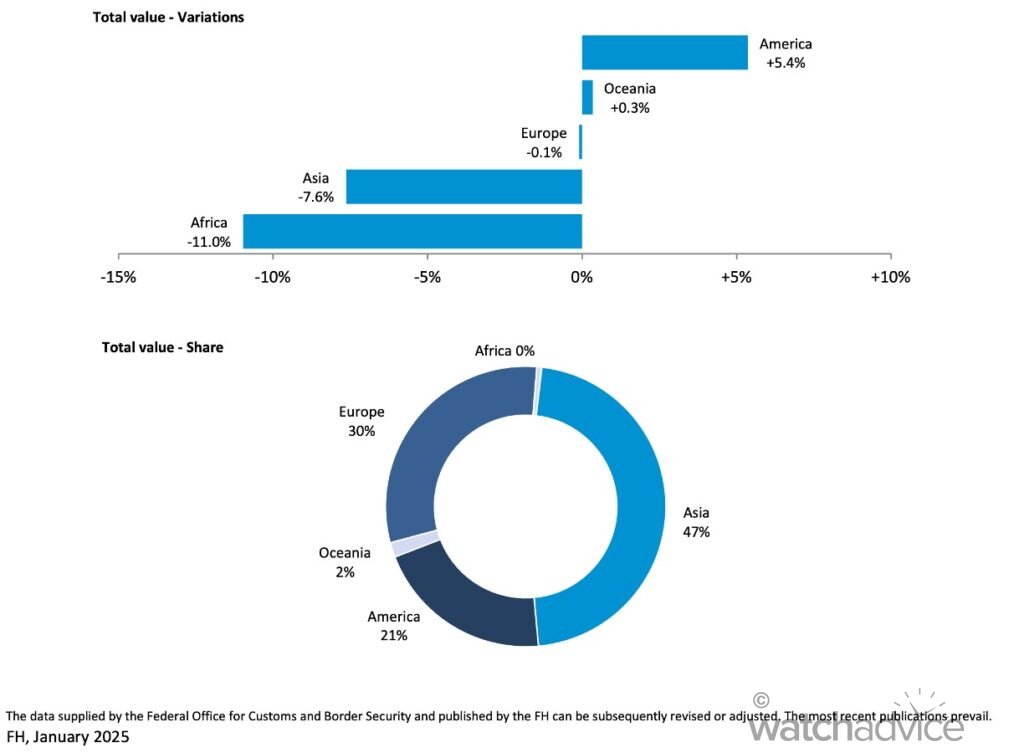

So, last year (2024) was an up-and-down year for the Swiss Watch Industry. According to the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, 2024 saw an overall decline of -2.8%, compared to a rise of +7.6% in 2023. In revenue terms, about 26 billion CHF (Approximately A$46b at today’s exchange rate) was generated in 2024, down about 700M CHF from 2023. This was primarily due to the economic slowdown across the globe and the drop in regions such as China and Hong Kong, which was significantly higher than in other regions.

And when you look at the company reports across a range of brands and groups, it would seem these figures hold true overall. Just note, that this is on average, but not for every brand. However, last year was a volatile year. A combination of inflationary issues across the globe affecting sales, mixed with the aforementioned exchange rate issues, as well as the China and Hong Kong markets, being significantly down, meant that profit levels weren’t what they were forecast to be, and operating margins were down on the year before.

On average, the operating margin across companies (with public financial reports) was about 10%. Just note, this is an average across a lot of brands so some brands and divisions will be lower and some higher. Also, note that interest and taxes are after the operating result, so the actual margin will be lower once interest and taxes are accounted for. What does all this mean then to you and me? Whilst we can’t access individual P&L statements for every brand and look at this by collection, what we can do is extrapolate these figures in an average scenario. Just to caveat this: It doesn’t take into account all the nuances of all brands and models such as precious metal pieces or if a brand does a lot more R&D than another.

So if a watch retails for let’s say, A$20,000 and we assume revenue and operational expenses, not to mention write-downs and losses are distributed equally across every piece (which in most cases it’s not), then we can work on this premise that a $20,000 piece from a major brand in 2024 with a higher than average margin of 15% will have around $3,000 or so baked in. On a less profitable business at 5%, then this is about $1,000. Now this scenario takes into account equal amortisation and cost distributions, but this will not be the case as some models will be sold at scale with smaller margins, and other pieces will have fewer units with higher margins.

Now, equal distribution of costs across models and product lines isn’t what happens normally. Different products would hold a different share of the operating costs based on a range of factors. In a real-world example from my previous career, one of the products that I looked after had a fixed cost of about A$1.6M per year, meaning the cost of the raw materials to produce it plus the salaries of the people who worked on it specifically. When the business rolled in shared expenses (all other business overheads like IT, insurance, wages of other employees not aligned to specific products etc etc), it made this a A$2.5-A$3M product. This is inevitably what the operating costs for the product were assessed at, and subsequently, profit margins were derived from. Fair? not really, but that’s business. I’m not saying that this is the case when it comes to a luxury watch brand, but it would be fair to say that each model line, department and division would have its fair share of operating expenses on top of the direct costs, like my example of the VC Overseas above.

The other aspect that needs to be taken into account is the distribution model of the brand. Some brands will sell directly to customers only, i.e. brand-run boutiques and online, whereas other brands will use retailers as well. This will also vary based on the market as in some markets and regions within, brands may or may not have a brand boutique and ONLY use retailers, meaning the average profit will be less due to selling units at wholesale vs retail.

As an example, a brand like TAG Heuer will sell via their own boutiques at retail as well as their online store but also use a network of retailers where they sell their pieces wholesale to them. If you look at a brand such as Zenith, here in Australia, they only use retailers to sell, as they have no boutiques. If you look at Seiko, then a majority of their pieces are sold via retailers and not brand boutiques (excluding online sales). To complicate this further, many brands are now selling selected models and limited editions via their online and boutique outlets only, so factoring in margins and profits per piece is even more complex.

And speaking of rental rates, boutiques can pay huge amounts just to have a presence in high-traffic or luxury precinct areas. As an example, according to Business Insider, Via Monte Napoleone in Milan now has rents as high as US$1,959 per square foot per year. So if your boutique is a nice sized 140 or so square meters, or 1,500 square feet, it means you’re paying in excess of US$2.93M per year in rent alone for one store in Milan. In the case of Sydney, along Pitt Street Mall or King Street (where many of the luxury boutiques are), stores can be paying up to A$1,195 per square foot per year, which using the store example above, equates to A$1.79M a year in rent. If we assume (for the sake of easy maths and not assuming too many specifics) an average sale price of A$12,000, then that boutique needs to sell 150 pieces a year just to pay for the rent if the full proceeds of each sale goes back to the boutique to cover costs. Obviously, this isn’t the case, and they have many other overheads to pay for as well as raw materials and everything else I’ve discussed, so that boutique now needs to sell a whole lot more to make a profit of any sort. You get the gist.

Some Final Considerations

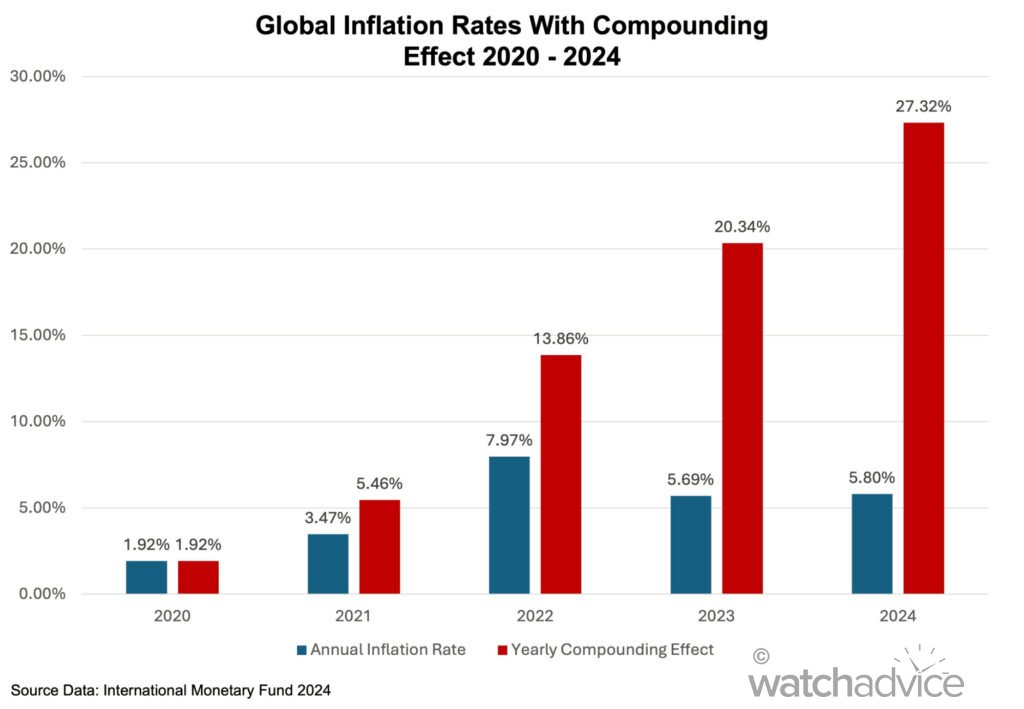

While I haven’t done a forensic analysis of each and every brand’s P&L (I’m not sure any brand will let me do that!), what I hopefully have done is given pause for thought around some of, but not all, the ins and outs of a watch brand and business. Yes, prices of watches have gone up considerably in the last 4-5 years, but so has everything, unfortunately, and this brings me to my final point, which is price rises and inflation.

If you look at the good old Rolex Submariner Date again, in 2020 when the new model 126610LN was released, it was A$12,900. Today, the RRP is A$16,900. That is a 31% increase in price during that time. Over that same period to the end of 2024, the overall increase in prices due to inflation in Australia was 20.5% (taking into account each year and the compounding effect). However, inflation figures only take into account certain variables, and not others, so in reality as we’ve all experienced over the past few years, things are now a lot more expensive. Again, I’ll mention that inflation is general and not specific, so while it may have been 20% compounded here in Australia, other countries will be more and some less and the same goes for industries as well. Globally, the average has been just over 27%, so an increase of 31% to a product that sells globally vs a global compounded inflation rate of 27.32% isn’t too bad considering.

All of this has wide-ranging impacts on all industries, not just the luxury watch market. Everything has a knock-on effect and in the case of Swiss watchmaking where most brands are operating globally, then every economic force, good or bad, has some sort of impact along the entire supply chain. Over the past few years, it meant higher prices due to high inflation, the downturn in consumer spending and confidence, conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, and the slowing of growth rates in China leading to massive pullbacks in the luxury spending of the middle class, not to mention rising raw material costs (gold as an example has risen 58% since 2020, almost triple inflation), wage increases and fluctuating global exchange rates.

So the next time you think a brand doesn’t need to increase its prices, or you feel that that piece you’re looking at doesn’t justify the price tag because “it doesn’t cost that much to make”, then have a think about this article, and if you ran a business that sold a product, (or if you in fact do run a business), what are all the elements and associated costs that go into designing, making, shipping, marketing and selling that product, and how much money you would make if you sold it for what the raw materials were/are?

And if you’re reading this article, and are a watch lover like many of us, then think about how cool it is we get to enjoy this industry and hobby, and like I always say, stick to what you can afford, and enjoy it for what it is. Remember, luxury watches are a want, not a need, and if you can afford to drop $5k, $10k or even more on a piece, you’re probably in a fortunate position already, or have worked and saved hard to purchase that special piece, so enjoy it!