Zenith is celebrating its 160th Anniversary this year, and we had the opportunity to visit the Manufacture in Le Locle to learn all about the brand Georges Favre-Jacot founded in 1865 and why the new G.F.J. with the Calibre 135 is so important for the brand.

This article is written in partnership with Zenith.

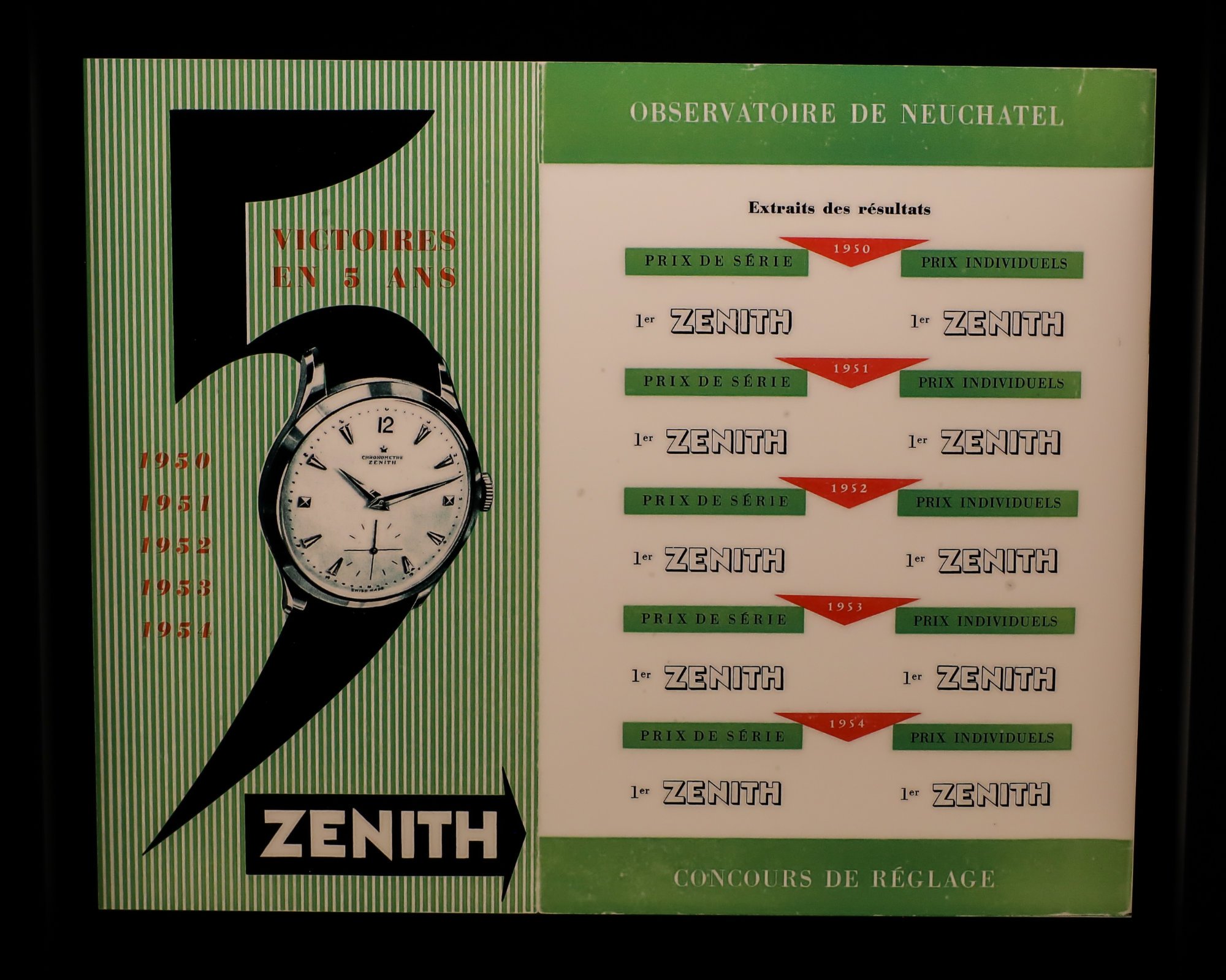

Out of all the Swiss watch brands on the market today, Zenith has one of the most interesting stories to tell. Not only has it survived the brink of collapse, but it was the first Manufacture to have vertical integration and all the manufacturing processes under one roof, which at the time, was unheard of in the cottage industry that was Swiss watchmaking. It was also one of the very few brands that were able to win five first-place prizes at the (then) coveted Nauchâtel Observatory Chronometry Trials with its Calibre 135 – a manual winding calibre with an oversized balance wheel that ticked all the boxes for the boffins at the Observatory, and passed all the tests with flying colours five years in a row! Not only this, but Zenith holds the prestigious title of being the most decorated watchmaker ever, with 2,333 chronometry awards to its name.

Knowing this, the Zenith Manufacture in Le Locle, just outside of Neuchâtel in Switzerland has been on the list to visit now for a while, and thanks to the team at Zenith, Watch Advice was able to spend a few days with the team over there and learn all about the history of Zenith, Georges Favre-Jacot as well as the importance (both historical and for today) of the Calibre 135 which can be found in the new Zenith G.F.J.

Swiss Hospitality

One of the aspects of Swiss people I love is their hospitality. Whether it is a watch brand showcasing the best of the brand, or the lady at the front desk of the hotel you’re staying in for a week in Geneva, I’ve always found the Swiss to be friendly, helpful, and tolerant of my ever slowly improving French – thanks Duolingo! So, flying into Switzerland early for Watches & Wonders 2025, thanks to an invite from Zenith to visit their Manufacture and see the new pieces, and the fact that they are celebrating 160 years this year, we were expecting that hospitality to be on show again, and unsurprisingly, it was.

Neuchâtel is a beautiful part of the world, situated right on the lake with clean, crisp air, it is very much like a picture postcard, as is the Hotel Palafitte, which was our home for a couple of days whilst on tour. I think Ben from Ben’s Watches (who was also with us, among others) summed it up in a video when he described it as “The Maldives Of Switzerland”. Stunning overwater villas, which in Summer would be perfect to jump into the crystal clear water of Lake Neuchâtel. Not in late March, however, when the air was 8 degrees Celsius and the water not much warmer!

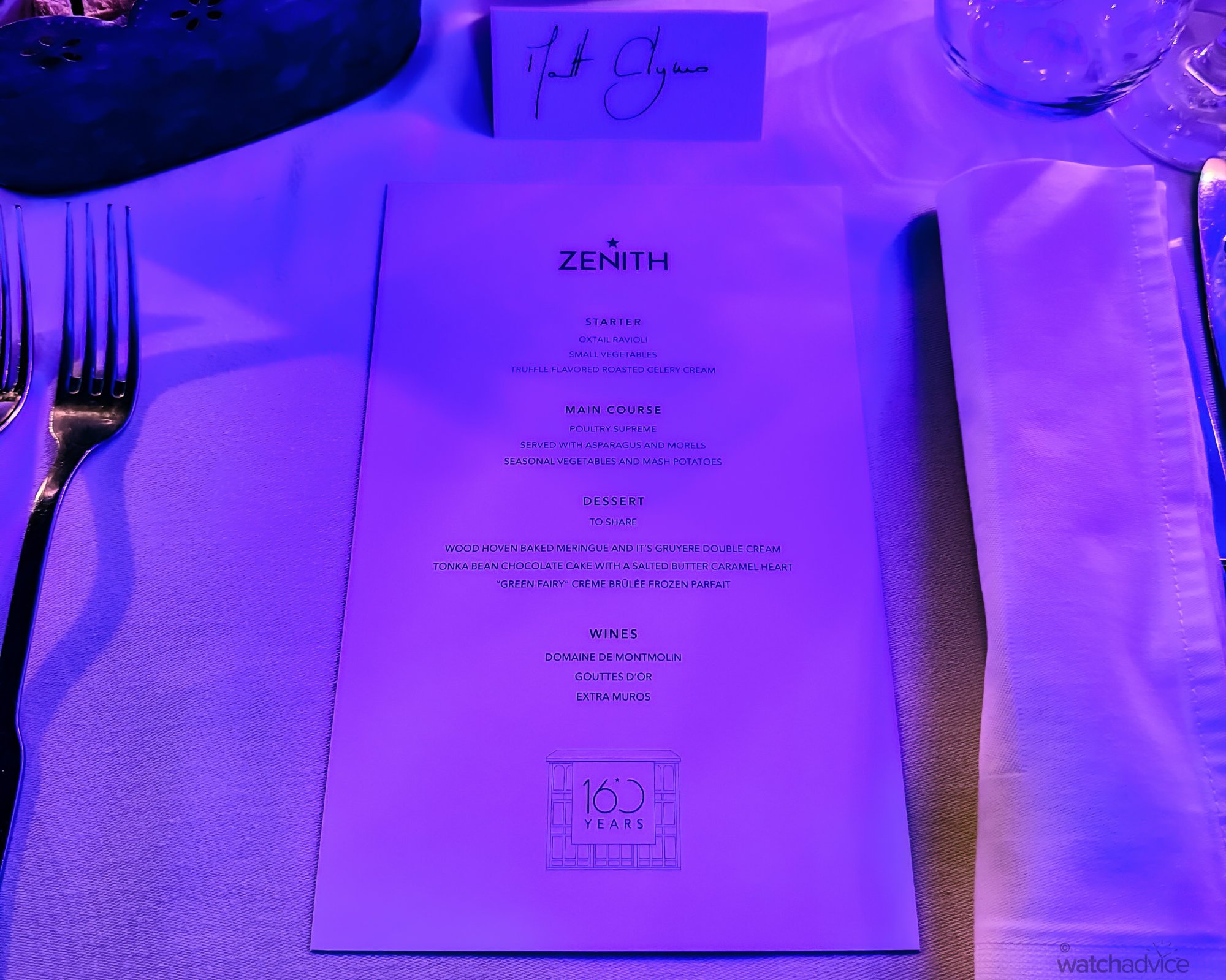

That night, after a couple of hours to shake off the 28 hours of travel, we headed to a 16th-century farmhouse in the countryside to enjoy a Swiss dinner, meet the wider team from Zenith in Le Locle and preview the new Zenith G.F.J. As we arrived, the entire farmhouse was bathed in Zenith Blue, which made for a spectacular first sight and experience for the evening.

After a good night’s sleep by the water, the next day we ventured from Neuchâtel to Le Locle to visit the Manufacture, still residing where Georges Favre-Jacot set up the brand 160 years ago. As blue is Zenith’s colour – representing the shade of blue when looking up to the highest point of the sky (the zenith), the Manufacture has been decked out in blue to both celebrate and let everyone know it is their birthday! Interestingly, as we were walking in, I noticed a plaque on the wall, which said “Ici sont deposees les cendres de Georges Favre-Jacot” meaning, here are the ashes of Georges Favre-Jacot. So it seems that a part of him is still within the Manufacture today.

The Manufacture

The Zenith Manufacture is on the same site where Georges Favre-Jacot set up the original business over a century and a half ago. Georges Favre-Jacot (G.F.J.) was only young at the time, 22 years old in fact, when he set his sights on his zenith, so to speak. He had a vision, after visiting the United States, that he could create a vertically integrated watch Manufacture and, in turn, create the “Perfect Watch”. This was a very unconventional idea at the time and one that landed him with a lot of ridicule from the industry. Back then, the Swiss watch industry was very much based around brands using specialists to create parts on spec, which were then brought into the Manufacture to assemble. Having one brand make and then assemble all the parts of the watch was unheard of, so G.F.J. was most definitely breaking convention. To do this, G.F.J. knew he had to build a place where this could happen. Le Locle was that place.

While the Manufacture has grown since the early days, it is still in the same location. In fact, you can see the old building, which now sits behind the newer buildings at the front, with the exposed red brickwork and both G.F.J. (which was what Zenith was known as until 1911) and Zenith written on the building. This is what is represented on the new front building today, and the pattern from which the new Zenith G.F.J. watch takes its design inspiration.

As alluded to, Zenith didn’t get its name until around 1911. Up until this point, the watches bore the name, or initials, of G.F.J. However, as the story goes, almost 50 years after the brand’s inception, Georges Favre-Jacot was working on a movement one night, and after its completion, he looked up to the sky, to the highest point (the zenith) and was inspired by the idea of space, the universe and the perfection of it. To him, it symbolised aspiration, achievement, and precision. All the ideals he wanted his watches to embody, and thus, he renamed the brand Zenith in order to have a constant reminder to always strive for the ultimate and highest standard in watchmaking.

Part of the Zenith Manufacture story, which is now well known in watch circles, is the turbulent time of the quartz crisis and how Zenith almost lost all of its old knowledge to progress. If it wasn’t for the decisive actions of one brave watchmaker by the name of Charles Vermot, it could have been lost to history. Thanks to him, it wasn’t…

The Attic

The quartz crisis hit the Swiss watch industry hard, and many brands either went under or had to pivot quickly and adapt to survive the initial years when quartz became all the rage, thanks to the highly accurate and inexpensive movements. Zenith was one of those brands that almost went under, and almost lost its rich past to this in the 1970s. In 1971, Zenith was sold to an American company, coincidentally called the Zenith Radio Corporation, which pushed the brand toward quartz and electronic watches. At the time, this made a lot of sense – why would you continue to make inferior mechanical pieces when you could make quartz watches? (Now, we know better!). But a pivotal point came when the brand was ordered to cease production of all mechanical watches and dispose of the tools in 1975. A passionate watchmaker, Charles Vermot, came to the rescue, although this wouldn’t be known for many years to come and just how important the actions of Mr Vermot were.

The quick-thinking Charles Vermot, having spent his life working with watches, and in the 1970s, on the famous El Primero movement, decided to take matters into his own hands and protect the movement. He took all the parts from the machines needed to make the El Primero calibre, catalogued them and proceeded to hide them in the Manufacture’s attic. These wouldn’t be discovered again until 1984 when the brand was back in Swiss hands and looked to revive mechanical watchmaking.

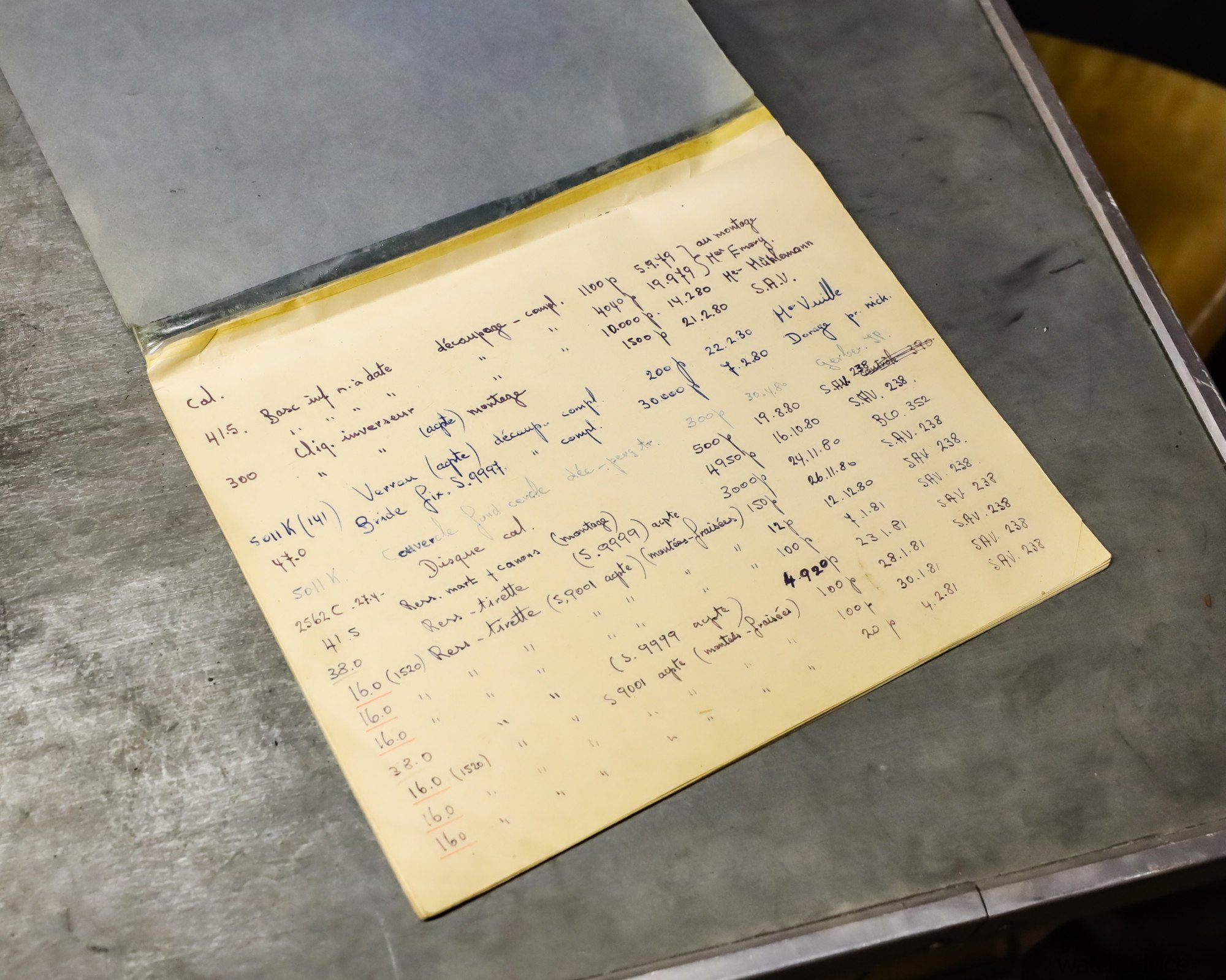

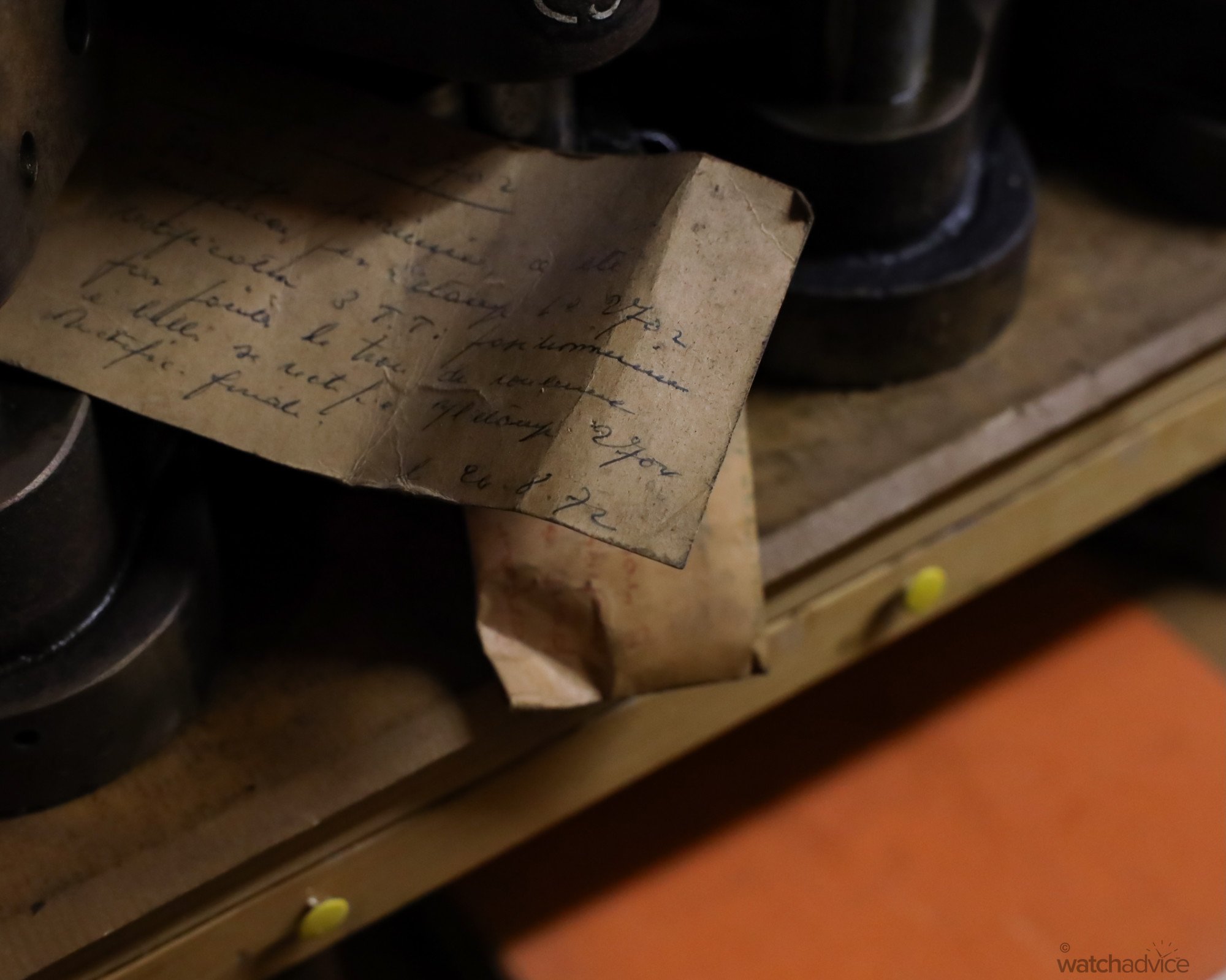

When you head up the stairs to the Attic and walk through the door, you realise just what an undertaking it was for Charles Vermot to painstakingly catalogue all the parts and then store them all away. When you think of an attic, you think dark and dusty, and lots of old parts stored on shelves, ready to resume service when the need comes. This vision would be correct in the case of the Attic at Zenith, albeit with small pockets of sunlight peeking through the windows built into the roof in the back section.

Walking through is like taking a step back in time. You can see all the parts of the machines, and via their reference and part numbers, what each of them was designed to do, for what Calibre and when they were stored. It is a great bit of preserved history that, thankfully, Charles Vermot had the foresight to take when news came through, that it was time to disassemble the machines and production was to stop.

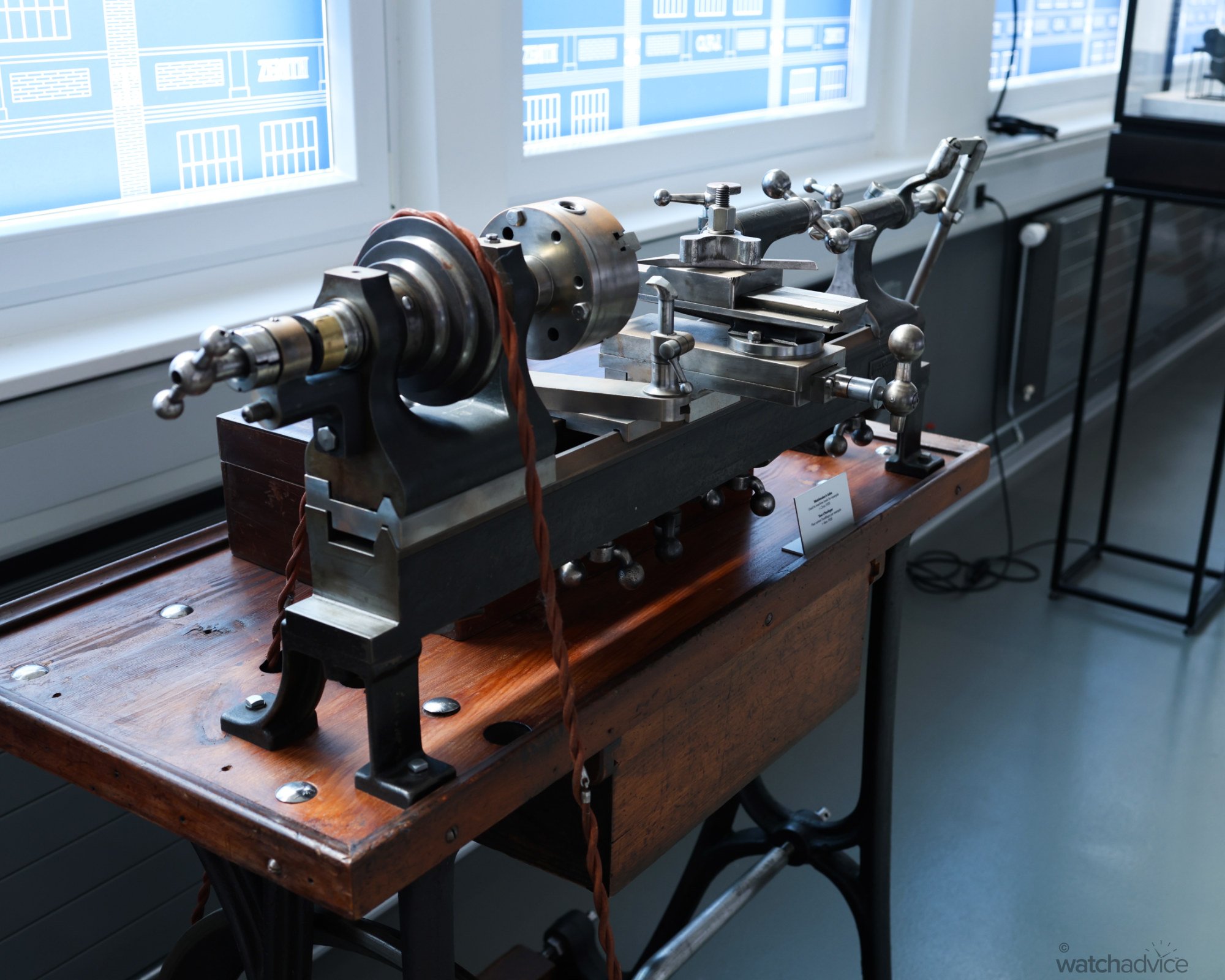

Heading out of the Attic, you can see some of the old machines Zenith has reassembled, which gives you a good idea of just how much watch-making has changed over the decades. Once, many of the parts were made by these hand and foot-driven machines to cut and shape the plates, bridges, dials etc, whereas these days, specialist machines now do the job more effectively and efficiently, where the finesse of hand finishing isn’t yet required. Think of cutting the raw metal into the shapes needed for plates and bridges, and machining out the raw shape of the case before these are passed over to the watchmakers to finish the polishing, beveling, and decorating before assembly.

A Walk Through History

Moving on from the Attic, Zenith has set up a small museum, or exhibition of sorts, that takes you on a journey back through the past 100 years or so of pieces created by Zenith. Head of Heritage for Zenith, Laurence Bodenmann, who has a wealth of knowledge of Zenith, guided us through its past, which you need to understand to fully grasp the direction Zenith is moving in with the new G.F.J. piece.

As you slowly walk through the exhibit, you come to realise that Zenith, in living up to George Favre-Jacot’s dream and mission of building the perfect watch, was one and the same – to be the best watchmaker, and the most accurate. This is perhaps why Zenith has won an impressive 2,333 awards for its movements. Everything from early marine chronometers to stopwatches and clocks used by the railways and postal service, through to the wristwatches on people’s wrists each day.

Above you can see some beautiful examples of vintage Zenith pieces with a Railroad Pocket Watch from 1907 and a desk clock chronograph used by the Swiss Postal Service from 1930-1960. Instruments like these were pivotal in keeping the country running on time, as both the railway and postal services were part of the backbone of most Western countries in the early part of the 20th century. Businesses and industry depended on them, and the railways in particular, thanks to industrialisation and the ability to transport people and goods across the country.

Below, we have some older Zenith Calibres. The first is the Calibre 20 1/2 N.V.I, which competed in the chronometry competitions in 1921, and in the second image, we’re looking at the Calibre 5011. This calibre was highly important to Zenith as a brand, as in 1967 it was awarded the most accurate calibre ever in the Neuchâtel Observatory’s history!

As you can tell, Zenith prided itself on being not only an integrated watch manufacturer, but also living up to G.F.J’s ambition of creating the best watches, or in his words, the most perfect watch. And this brings us the the Calibre 135, and its modern reinvention in the form of the new Zenith G.F.J.

The Calibre 135

Developed in 1948 by Zenith’s Chronometry expert, Ephrem Jobin, the calibre 135 was designed specifically to compete in Observatory Trials – competitions that pitted the best watch Manufactures against each other to see which movements were the most accurate and reliable through a series of tests. In the early to mid-1900s, these trials were massively important to watch brands as accuracy and reliability were key selling points. It was called the Calibre 135 due to the size of the movement being 13 lignes in size (30mm in modern metrics) and 5mm thick, which was significant as movements back then had to fall within this size limit to compete at the Observatory trials, of which the Calibre 135 was designed for.

The 135 was a manual winding movement with 40 hours of power reserve, and its main feature was the oversized balance wheel, which beat at 2.5Hz / 18,000 VpH, allowing the high accuracy of the movement along with efficiency. The screws on the balance wheel also allowed the watchmakers to more finely regulate the movement, which aided in the movement being so successful.

It is the most awarded and one of the most accurate movements produced by the Manufacture. From 1950-1954 (inclusive), it won the prestigious Chronometry Awards at the Neuchâtel Observatory for those five years in a row. All up, the Calibre 135 collected a total of 235 chronometry prizes between 1949-1962, and for this reason, is perhaps the most historically important movement for the Le Locle brand.

Due to the success and ultimate significance of the Calibre 135, it is no surprise that Zenith decided to bring it back after more than six decades. Now, this is not the first time Zenith has done this. In 2022, Zenith, in collaboration with Kari Voutilainen, brought back a special limited edition run of 10 pieces – the Calibre 135 Observatoire, which was sold via Phillips in association with Bacs & Russo. These 10 pieces used original competition-grade 1950s Calibre 135 movements that had been preserved by Zenith, which were then restored and finished by Voutilainen by hand. In turn, Zenith created elegant, vintage-inspired cases and dials that would appeal to collectors and aficionados alike.

Taking inspiration and design cues from the commercial watches from the 1950s that housed the Calibre 135, the watches featured a 38mm platinum case and a black guilloché dial, combining vintage aesthetics with contemporary craftsmanship. Priced at CHF 132,900 each, all 10 pieces were sold exclusively through Phillips and were quickly snapped up by collectors. There was an 11th version made, however, created with distinct features such as a niobium case, a salmon guilloché dial, and a movement finished in a rose gold-tone. This one-of-a-kind watch was auctioned at the 16th Phillips Geneva Watch Auction in November 2022, and it achieved a remarkable sale price of CHF 315,000, with all proceeds donated to the Susan G. Komen® Foundation to support breast cancer research and awareness.

Reinventing The Calibre 135

Having this insight into the history of the Calibre 135, if you’re like us, you will now have a new appreciation of what this movement means for Zenith. It also allows you to understand why Zenith has brought it back and re-engineered it for modern watch enthusiasts in celebration of the brand’s 160th Anniversary. And to be honest, from all the feedback we heard at Watches & Wonders, it seems Zenith has knocked it out of the park with this piece. However, it is not just the fact that the Calibre 135 has an amazing history that makes the movement in the G.F.J. so remarkable; it is how Zenith has been able to re-engineer it for a 21st-century buyer, something that is not as straightforward as you think. You can’t just take the old movement and make it in modern materials, you need to design it from scratch using the design blueprints and specs as the guide to create the entirely new Calibre 135…which is what Zenith did.

While at the Manufacture, we spoke extensively with key personnel involved in the G.F.J. project, like Zenith’s Chief Product Officer, Romain Marietta and Creative Director Sebastian Gobert, not to mention a swath of watchmakers and other project leads. As mentioned, reviving a movement and making it to modern standards isn’t just about taking the old design and updating the materials. With new and modern materials come challenges, as do things like increasing the power reserve to 72 hours from the original 40 hours and making it less susceptible to magnetic fields. All the things that a modern watch movement needs to be these days.

The project took several years from inception to completion, and with this, millions of dollars in R&D, testing, prototyping, and refining, not to mention training the watchmakers to make and assemble the movement. However, Zenith wanted to make this watch a new foray into high horology, which meant the watch and the Calibre 135 needed to have a greater level of finishing as well as exceptional accuracy. On the accuracy side, the new Calibre 135 is both COSC certified and then it goes further with Zenith guaranteeing an accuracy of +/- 2 seconds a day, putting it in the same league as master chronometer certified pieces.

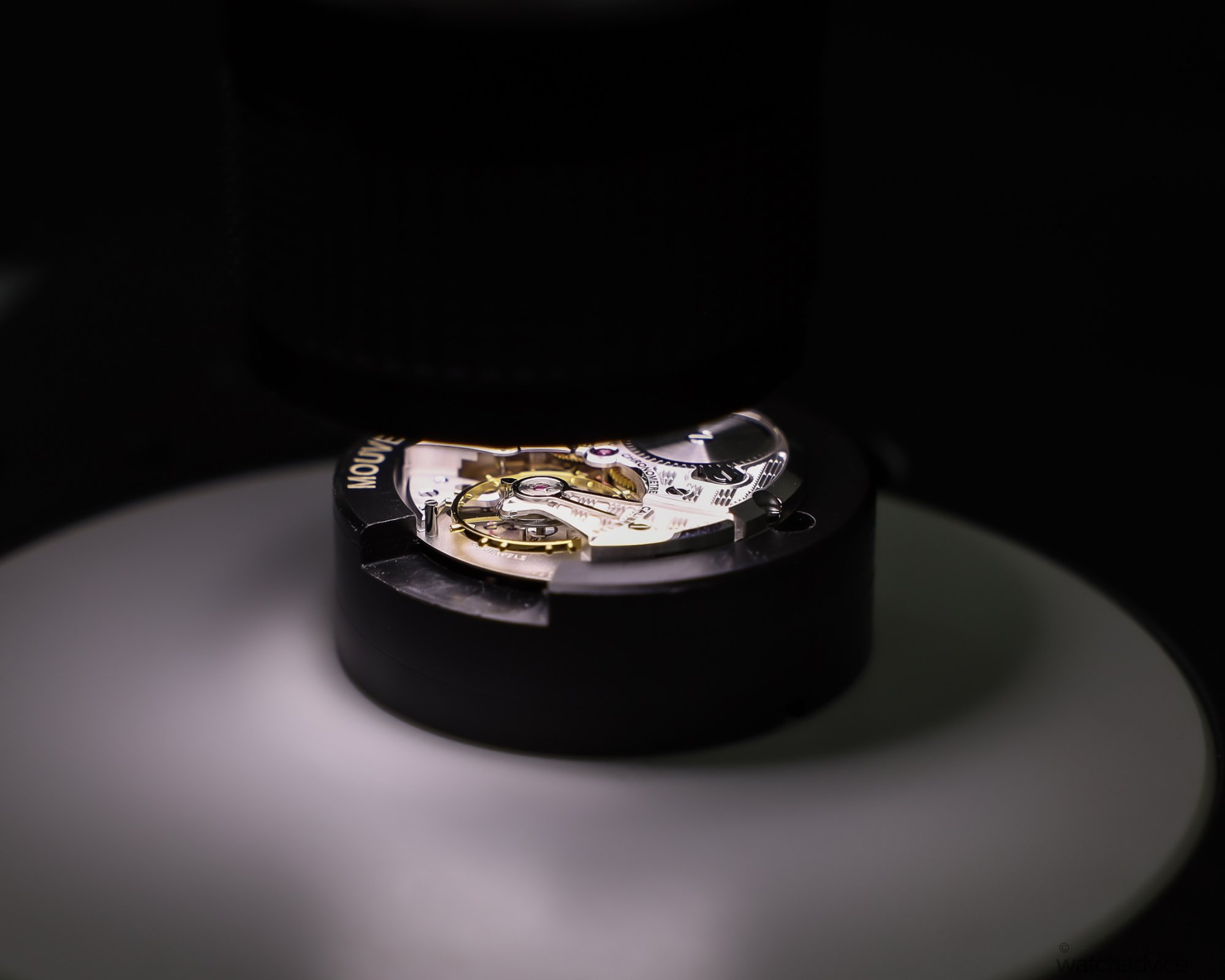

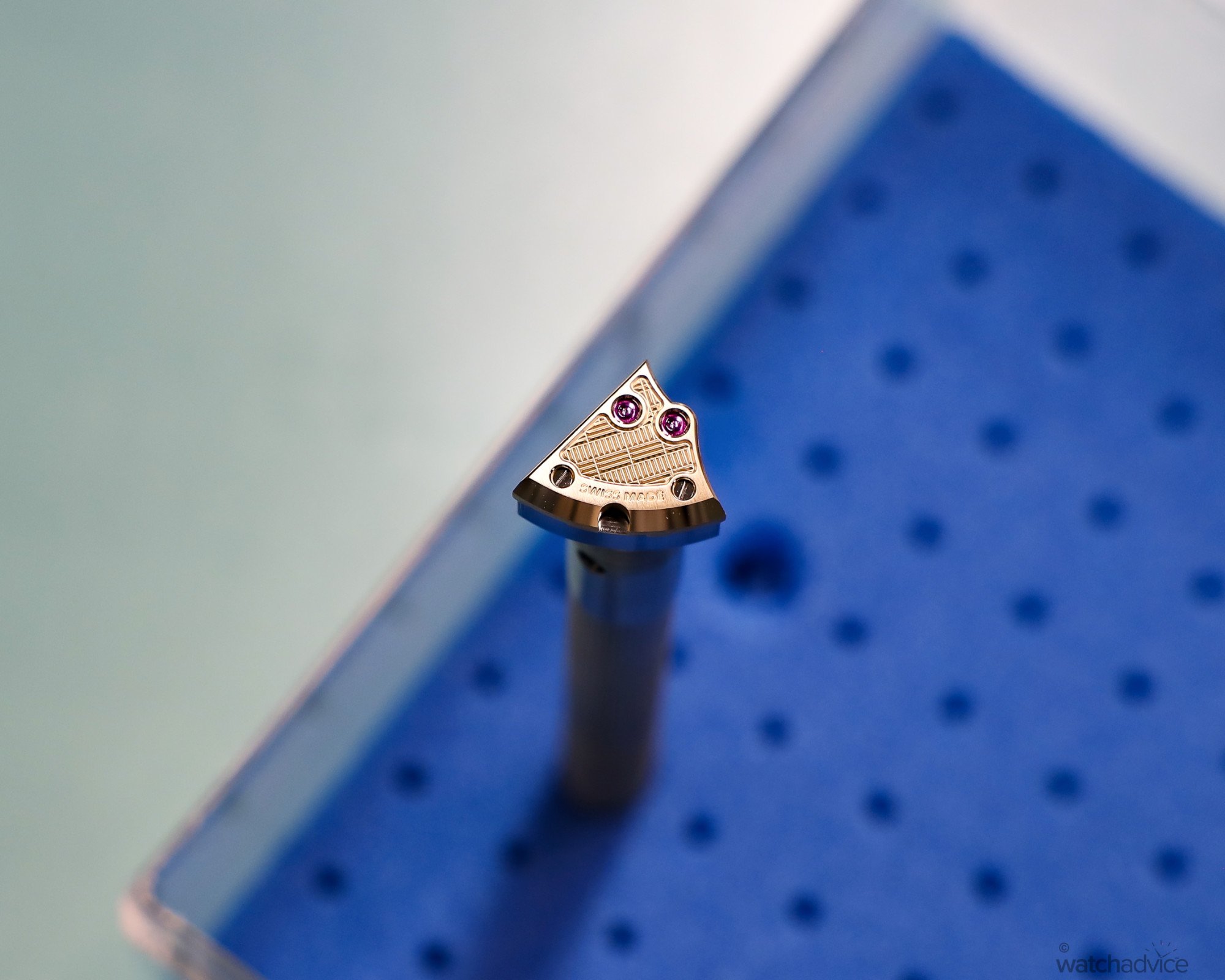

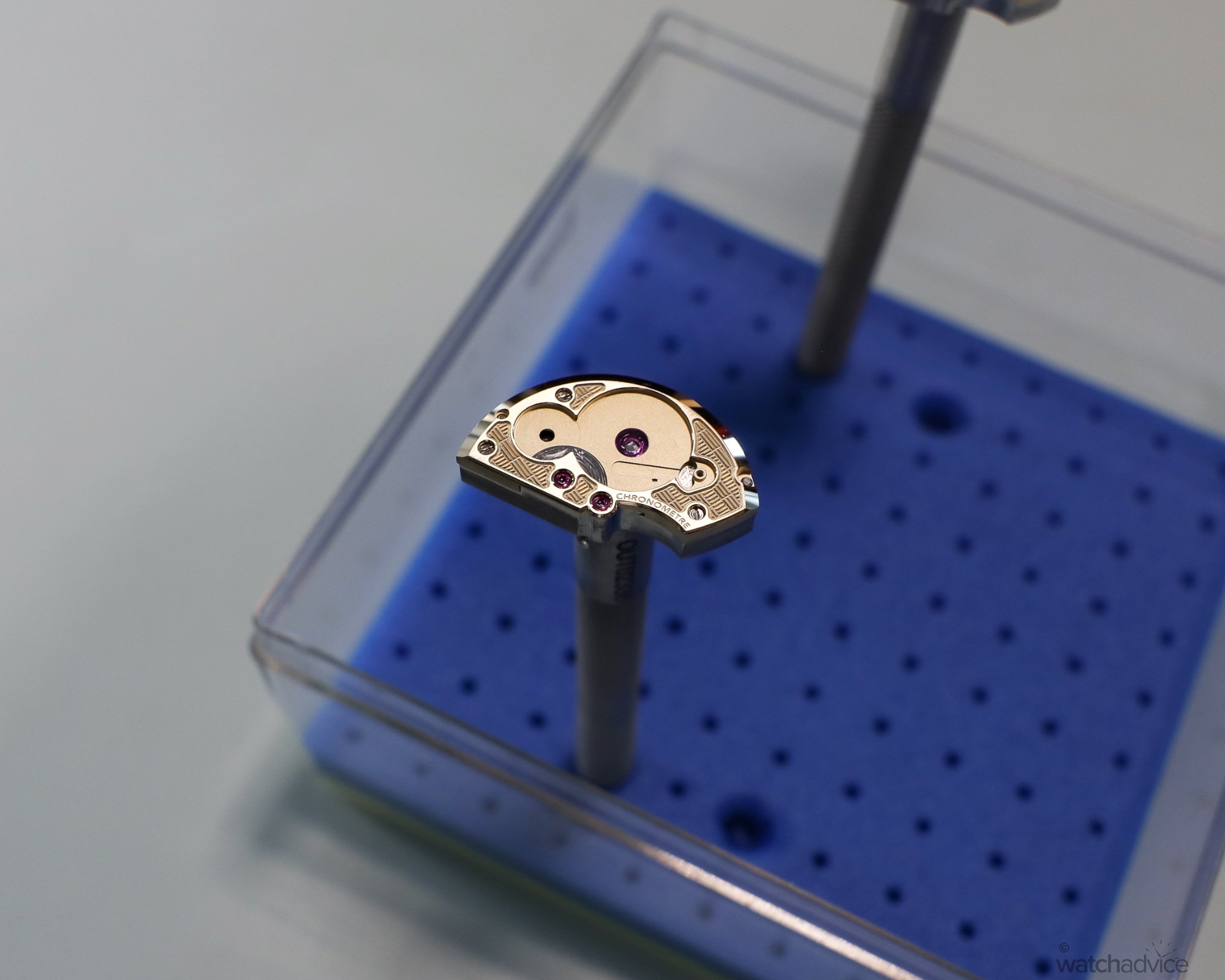

When it comes to finishing the movement, Zenith has taken this up a notch and crafted a movement that is quite stunning to look at. The bridges are finished in a “brick” guilloché finishing, inspired by the distinctive façade of red and white-painted bricks of the Zenith Manufacture (refer to the start of this article). These are also hand-bevelled to create a polished englage on each bridge, which is done by hand, the traditional way – rubbing different pieces of soft wood against the metal, over and over again until a high polish is achieved. We were lucky to see this in action and speak to one of the artisans whose job it is to do this, and from what they told us, it takes several hours to do just one of the bridges, as shown below.

Above you can see some of the bridges on the new Calibre 135 with a high level of finishing via the etched brickwork motif on the top, and the hand-anglage around each of the edges. Below, one of the artisans is hand-polishing a bridge with the small wooden rods (in the second image) that are used to create the high polish. This technique is old and meticulous, and with only a couple of people doing the decorative work, the production of the Calibre 135 is limited based on the time it takes to finish the movement.

The result is a movement that is very well finished, and does justice to the original Calibre 135 and then some. You can see in the below image the brickwork motif on the bridges, the solarised mainspring barrel, oversized rubies and black polished screws along with the large balance wheel with the fine adjustment screws to ensure a higher level of accuracy in a movement that beats at just 2.5Hz. In addition to the balance wheel screws, the movement retains the V-shaped double regulator that aids the ability to get the movement beating exact.

Now I couldn’t talk about the Calibre 135 without mentioning the G.F.J. that houses it. We’ve covered the release of the piece here, and I chose this piece as one of my standout pieces this year at Watches & Wonders based on the aforementioned details. But the Calibre 135 is just one part of what makes this piece a standout.

The Zenith G.F.J.

Entering the Haute Hologerie world means you need a watch that is representative of this, and Zenith has done just that with the G.F.J. Cased in a 39mm platinum case, which has vintage style cues and finished as well as the movement, Zenith has gone into a lot of detail to create a piece worthy of the 160th Anniversary.

Zenith has given a lot of thought to the detail in the G.F.J. and speaking with Sebastian Gobert, Zenith’s Head of Creative and Design, he tells us about these at length. First, they wanted to create a piece that spoke to both the DNA of Zenith and also incorporated a range of design cues inspired by the Manufacture itself. This is why they have chosen the blue in the dial (Zenith’s colour), and not one, but three shades of Zenith Blue. The outer track is a darker blue, which is Guillochéd in the style of the brickwork on the Manufacture, and aligns with the guilloché on the movement. If you look closer, the hour indices have been designed to mimic this as well.

On the inner part of the dial, Zenith has sourced ethical Lapis Lazuli. I was not aware until my visit that most Lapis Lazuli comes from mines in Afghanistan, which if mined in the last decade or so in the region actually assists in funding extremist groups. For this reason, Zenith has been very careful about the sources or origin and making sure it is traceable and ethically mined. The small seconds dial is a blued Mother Of Pearl which acts to break up the Lapis Lazuli and adds another layer of texture and shade of blue to the dial.

The case itself is a combination of brushed and high-polished and has several stepped layers to it. Starting with the bezel which is sloped down to the upper case, this is then stepped as well to give it separation from the main case. The main case has been shaped so there is a stepped bevel around the entire case edge and lugs and the flat side of this is brush-polished to create a textured contrast.

Zenith is also giving people the option of a full platinum bracelet to complement the platinum case. The bracelet also takes design inspiration from the Manufacture brickwork, with the inner links etched in opposing directions to create the brickwork pattern. You will also notice that the bevelling on the edge of the case flows through to the bevel on the edge of the bracelet too, giving it uniformity and continuity all the way from the case edge down.

All Good Things Must Come To An End

With a full day well spent in Le Locle, learning about the history of Zenith, its founder Georges Favre-Jacot, the record-breaking Calibre 135 and how one man saved the mechanical knowhow of its past to be revived when needed, we boarded the shuttle and said goodbye to the wonderful people we met. The one thing that I am always amazed by, perhaps I shouldn’t by now, is that so many of the people who work for the watch brands in Switzerland are so passionate about the industry and the brand. This isn’t just lip service either as many have worked for them for 10, 20 and even 30 years. Zenith is no different.

While it is a brand owned by LVMH, Zenith is essentially treated like a boutique or independent brand. They are not making hundreds of thousands of watches a year like some, it’s in the range of about 10,000 – 20,000 pieces or so a year. The new G.F.J. signals a new era for Zenith, something I’ve commented on openly and with people at Zenith. Low production runs, high-end finishing and more focus on craftsmanship and quality taking inspiration from their highly awarded past. While this piece is limited to 160 units, it will undoubtedly be the start of something much more for Zenith, and I’m looking forward to seeing what this will be!

This article was written as part of a commercial partnership with Zenith. Watch Advice has commercial partners that work with us, however, we will never alter our editorial opinion on these pieces or brands, a fact that is clearly communicated to the brands when entering into a commercial arrangement. At Watch Advice, we categorically do not sell outcomes or our editorial integrity. We will never say a watch is good when it’s not, and our articles such as this are all our own experiences and first-hand accounts.