In this article, we take a look at one of the most iconic designs in watchmaking and why there won’t be another like the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak!

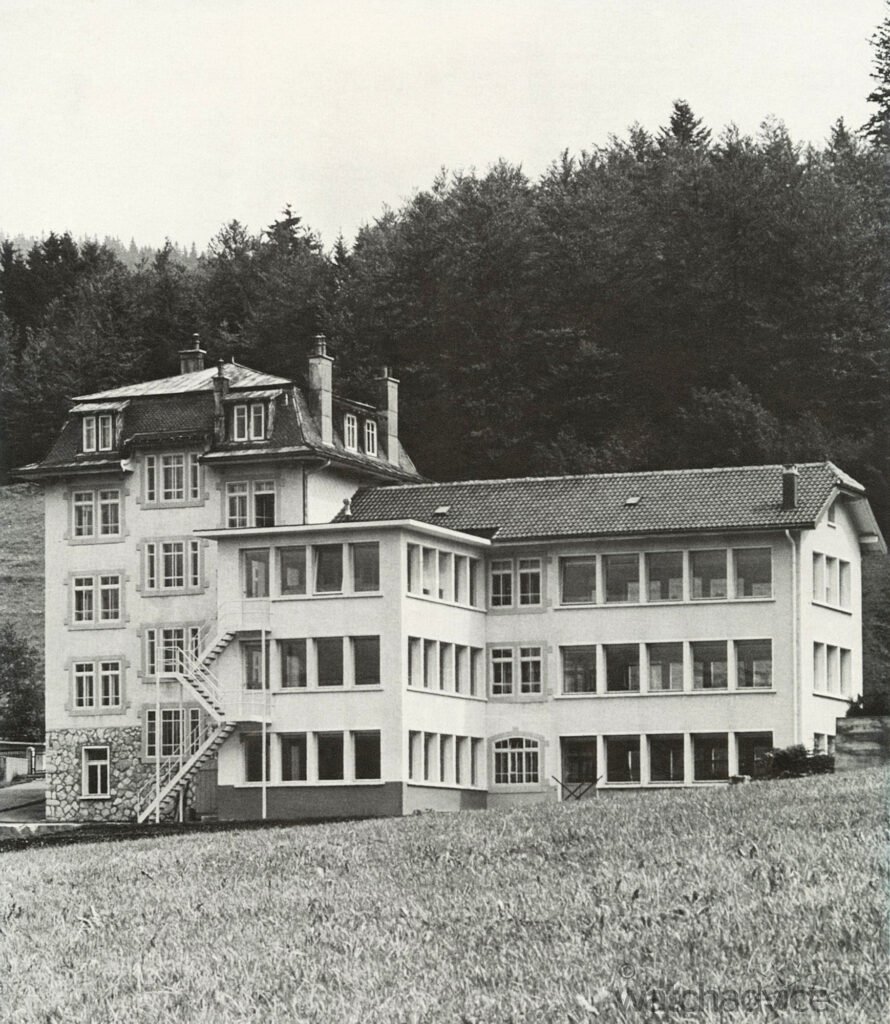

Craftmanship and attention to detail are some of the cornerstones of Audemars Piguet’s success. Founded in 1875 by Jules Louis Audemars and Edward Auguste Piguet in Vallée de Joux, Switzerland, the brand is one of the most respected and produces timepieces that are sought after not only by collectors but also by new watch enthusiasts. In the early years, the brand quickly gained recognition for creating complex timepieces, and as time progressed, it became known for creating some of the first-minute repeating timepieces (see our article on minute repeater complication here!) along with developing the first perpetual calendar with leap year indicator (see our article on perpetual calendar complication here!).

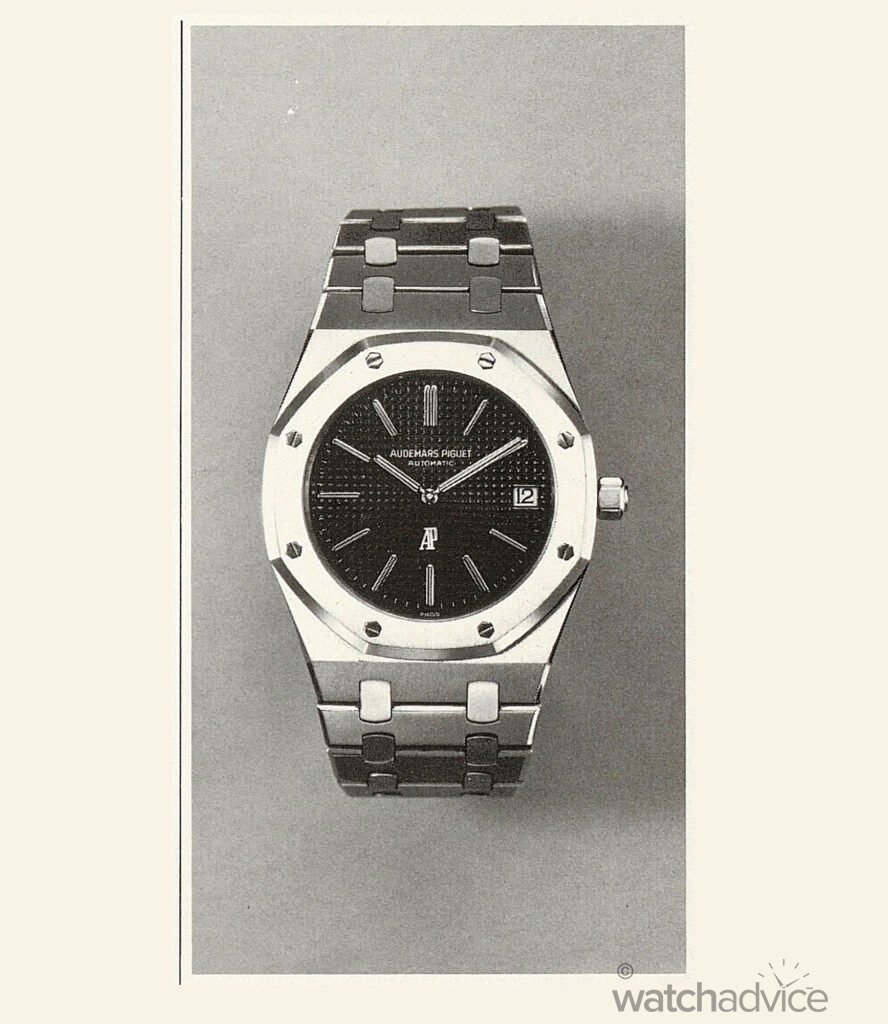

However, none of these innovations or timepieces put Audemars Piguet on the map as their Royal Oak has. The Royal Oak has risen to such a level of iconic status that it’s become one of the most sought-after models to add to one’s collection. The Royal Oak became a game changer in the world of the luxury watch market. At the time of it’s release, the timepiece immediately shifted the market, as it was the very first high-end luxury sports watch to be presented on steel (although the first Royal Oak was actually white gold!)

Chamath Gamage (WatchAdvice Founder) with his Royal Oak 15202ST

It’s also safe to say that the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak is the definition of timeless design. From its creation to the modern Royal Oak, the overall design has remained the same, bar new movements and material changes. This is because it has such a unique design. From the 8-sided bezel and the tapisserie dial to the integrated bracelet, it incorporates different elements that aren’t what you find on traditional timepieces, making it stand out from the crowd. When the Royal Oak was first released, these design elements were indeed unique, let alone found on a singular model, especially a “sports watch”. The Royal Oak’s design strikes the perfect balance between sportiness and elegance, allowing one to wear the watch on many different occasions. The timepiece’s aesthetic design has made sure that it stays relevant over the decades and never goes out of style, even adapting to changing fashion trends without ever losing its core identity.

One of the latest Royal Oak timepeices, the new Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon Openworked blends technical complexity with contemporary design!

As I’ve mentioned several times already, the Royal Oak is a loved timepiece sought out by high-end collectors, watch aficionados and celebrities alike. This is down to the Royal Oak’s status as a luxury symbol, its distinctive look, and Audemars Piguet’s being a highly respected brand in the world of horology. I have already covered Celebrity Watch Spotting Articles where we look at celebrities spotted with the Royal Oak and its variants, or even celebrities with entire collections of Audemars Piguet timepieces, including none other than John Mayer and his six-million dollar Royal Oak Collection (click here for article!), Daniel Ricciardo and his 18k Yellow Gold Royal Oak (click here for article!), Chris Hemsworth’s stunning trio of Royal Oak’s (click here for article!) or the Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar in blue ceramic and the celebrities spotted with it (click here for article!).

With the Royal Oak’s widespread popularity, let’s explore its origins and learn how one last-minute phone call the night before the 1970 Basel Fair led to the creation of one of the most iconic timepieces in watchmaking history.

Birth Of A Legendary Icon

Before we get into the birth of the Royal Oak, it’s important to get an understanding of where Audemars Piguet was as a company. Before Royal Oak’s creation, Audemars Piguet was experiencing a rise in sales and popularity, as it recorded the strongest 20 years of growth in the brand’s almost century-long history. In two decades, the growth of the company had gone from 35 to 84 employees – of whom 67 were active at the workbench – and had increased its production almost tenfold to 5,500 watches per year.

The brand, at the time of Royal Oak’s origins, was at the helm of the founding families’ second and third generations, represented by Paul Edward Piguet (1890–1979) and Jacques-Louis Audemars (1910–2002) and had been run by Georges Golay (1921–1987). Georges Golay’s role in the Royal Oak story was a vital one, which we’ll touch on later. He was a visionary entrepreneur, the son of a farmer and a native of the Vallée de Joux. Since his arrival at Audemars Piguet in 1945, he wanted to modernise the brand as much as possible.

Audemars Piguet and Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH)

With Audemars Piguet’s expansion leading to increased production, Georges Golay had to rethink how to distribute the timepieces, especially internationally. Considering that the company’s location was in a small mountain village, it would be difficult for the brand to distribute the watches effectively. The solution lay in signing a partnership with Swiss watchmaking giant Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH). SSIH was one of the leading watch manufacturers in 1970, with 4.6 million watches sold. SSIH had almost 7000 staff, and had controlled 20 brands, with the watches being distributed through 150 agents and 15,000 retailers.

In the 1960s, SSIH needed more high-end timepieces to offer alongside the existing flagship Omega watches to its clientele, and Audemars Piguet, being a high-end watch manufacturer, needed to expand its distribution network. It was the perfect pairing and a no-brainer for Georges Golay. After almost a year of negotiations, an agreement between SSIH and Audemars Piguet was signed on February 5th, 1969. The core of the agreement was that Audemars Piguet would retain its independence with its capital and manufacturing while using SSIH agents to distribute the watches.

The Three-Musketeer Agents Of SSIH

The agents in charge of distributing Audemars Piguet’s timepieces included some strong personalities such as Carlo de Marchi (Italomega, Turin, Italy), Charles Bauty (Gameo, Lausanne, Switzerland) and Charles Dorot (Brandt Frères, Paris, France). Audemars Piguet states that According to Martin K. Wehrli, who joined Audemars Piguet in 1971 and served as sales manager and then Director of the Museum until 2012, these three agents were nicknamed “the three musketeers”.

It is stated that on April 10th, 1970, Georges Golay met with the “three musketeers”. While the exact contents of the discussion cannot be recalled, it is known that the agents “challenged” Georges Golay to create a stainless steel watch in tune with the modern market. Georges Golay states that “The Royal Oak was conceived in 1970, at the suggestion of general agents who had reservations about the marketing value of gold alone for the promotion of high-prestige timepieces – a view which I believe is no longer valid. They did ask us to design a stainless steel wristwatch more in tune with the way we live today. We had to invent a model both sporty and stylish in spirit, suitable for evening wear and for the daily activities of today’s man of taste.”

Audemars Piguet & Gérald Genta Collaboration

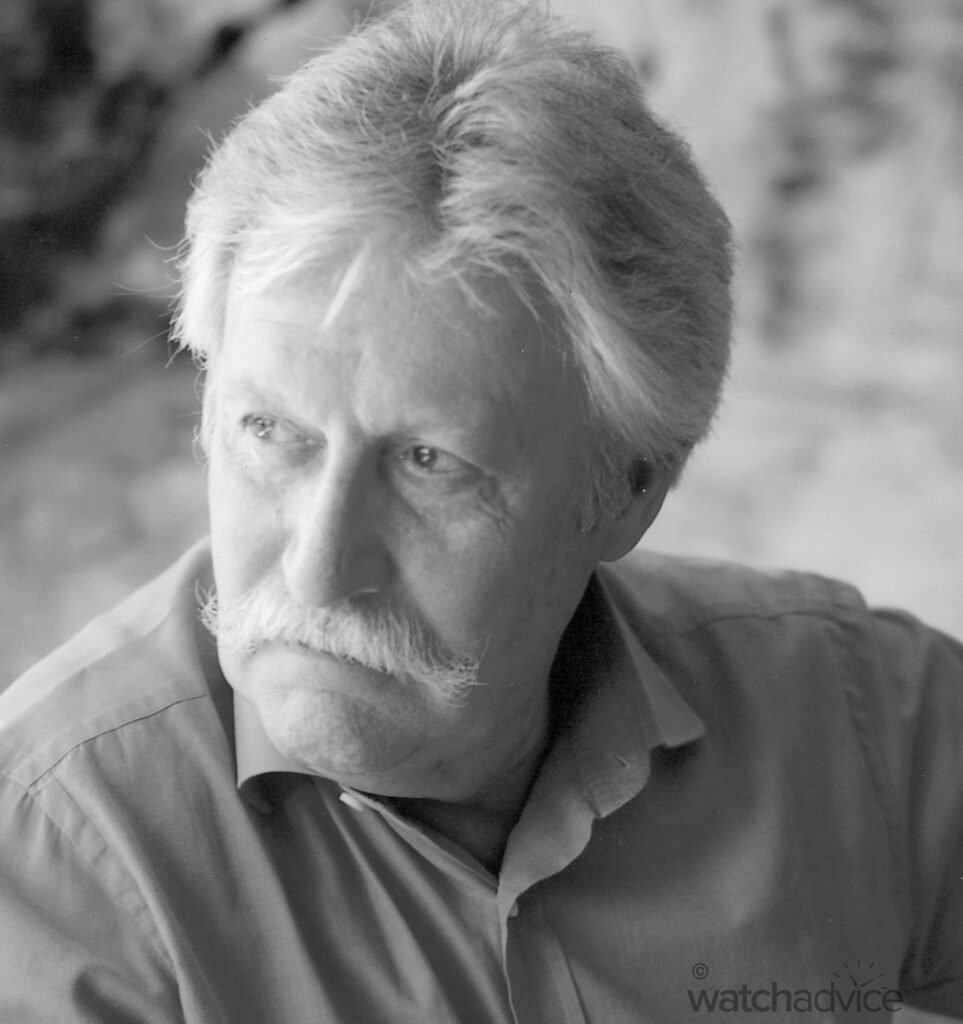

The story then goes that Goerges Golay, the day before the 1970 Basel Fair, called the renowned watch designer Gérald Genta. Genta would remember that 4 pm phone call for from Golay for the rest of his life. Genta states, “The Managing Director of AP who – with all his powerful intonation, natural authority and beautiful accent from the Vallée de Joux – said: “Mr. Genta, we have a distribution company that has asked us for a steel sports watch that has never been done before – and I need the design sketch for tomorrow morning.”

However, before we dive deeper into Genta’s work for the Royal Oak, it’s only right to understand the man Genta was and how big of an influence he was in the world of horology.

Born in 1932, Gérald Genta was an Italian designer and trained jeweller who also had expertise in the watchmaking world. During the 1950’s Genta sold hundreds of watch designs to a number of brands, which included the revised design of the Omega Constellation timepiece (1959). Later in his life, after working with Audemars Piguet, Genta earned himself the nickname “Picasso of Watches,” as he went on to design watches such as Patek Phillipe’s Nautilus (1976), revisited IWC’s Ingenieur (1976), or created the Bulgari Bulgari (1977).

While Genta worked for various companies in creating and imagining new timepiece designs, the role of a “watch designer” technically didn’t exist in the 1960s. As Audemars Piguet recalls, “Only a few “stylists” or “model makers” designed watches, among other everyday objects: chairs, cars, utensils, etc. The first to devote themselves solely to watchmaking and to make a name for themselves – such as Gérald Genta, Jean-Claude Gueit (Piaget) and Jean-Daniel Rubi (Patek Philippe), who paved the way for Jörg Hysek, Emmanuel Gueit, Claude Emmenegger.”

Audemars Piguet’s beginnings as a “small company” meant employing a few dozen people and producing one-off watches or tiny series. This meant that design projects were created from personal, often informal collaborations, nurtured by friendships between watchmakers and case-makers.

The Royal Oak wasn’t the only time Gérald Genta has worked with Audemars Piguet. The watch designer worked with Audemars Piguet in the 1950s, having sold watch designs to the brand back then. Genta continued his work for the brand in the 60s as well, creating timepieces with refined geometrical shaped cases, such as Model 5179, asymmetrical 5182 and 5199.

From the above pictures, we can already get an idea for the “out-of-the-box” thinking Genta had and gain a much better understanding of the artist’s design style, especially when it comes to the Royal Oak.

From the 1960s onwards, the relationship between Gérald Genta and Audemars Piguet grew much stronger. During one of his final interviews in 2011, Genta stated, “Everyone has their own taste, their own ‘vibrations’. Those I acquired at Audemars Piguet led me to develop a law of aesthetics and architecture corresponding to something intensely physical. The watch must adapt to the wrist, and it has to fit smoothly under a shirt cuff.” He added, “We were like a tandem, Georges Golay and me. If he was in agreement about something and I wasn’t, we didn’t make the model… We were in complete symbiosis.”

The relationship between Gérald Genta and Goerges Golay was that of best friends. This is why when the phone call came for Genta on the eve of the 1970s Basel Fair, he was ready to drop everything and get the work done, to produce a concept design to take the world of Horology by storm.

The Birth Of A Legend

Upon receiving the phone call from Goerges Golay, Gérald Genta immediately got to work. However, things could have almost gone awry really fast, as the designer stated that “I incorrectly understood him to have said ‘whose water-resistance has never been done before.'” One would like to imagine what the Royal Oak design would have been like if Genta had not designed a watch based on water resistance.

Genta took inspiration for the Royal Oak design from divers being fitted with the helmet on Geneva’s Pont de la Machine. Genta took the 8 bolts and the rubber seal on the helmet and converted this into a watch case design. His thinking was, “If the screws holding the faceplate were strong enough to ensure a watertight seal on the helmet, surely they must be capable of doing the same for a watch.“

Genta says that the Royal Oak’s bezel was shaped like an octagon as he needed to fit the eight hexagonal screws, which required space. The waterproof seal was an extremely substantial lip-type seal, which was located between the bezel and the monocoque (monohull) case. The screws were designed in a hexagonal shape so that they could be “embedded” into the bezel, preventing them from turning when the screws were locked from underneath (caseback).

The ingenious designer then goes on to explain that “Furthermore, I designed the integrated bracelet which was unprecedented, with tapering intermediate links that made it extremely hard to produce; the dial with hands and hour-markers delicately inlaid with luminous material; the sunburst cobalt blue dial base adorned with Clous de Paris guilloché pattern, complete with a smoky effect as the shade would otherwise have been slightly commonplace. I had to come up with all that in one night! It was a crazy thing; personally, I don’t know by what magic it was possible to create such a thing in one night. It was quite amazing!”

Oliver Audemars, Vice-Chairman of Audemars Piguet’s Board of Directors, representing the fourth generation of the brand’s founding families, states that the hexagonal screws were indeed an iconic and unique design at the time when the watch was first presented. Displaying the screws was indeed a disruptive act, a manifesto for showing mechanical resistance, technicality and solidity. Since it is impossible to turn a hexagonal screw, as it is embedded into the case, the screwed-down case design became a metaphor for a “safe”. This is all the more true for the Royal Oak, as inside the watch, the movement housed a partially gold movement, making it seem like the Royal Oak is protecting a traditional and mechanical treasure. The Royal Oak, represented so much when it was released. At a time when the quartz crisis was taking place and threatening the whole mechanical watchmaking industry, the Royal Oak stood proudly in the face of adversity as a watchmaking hero.

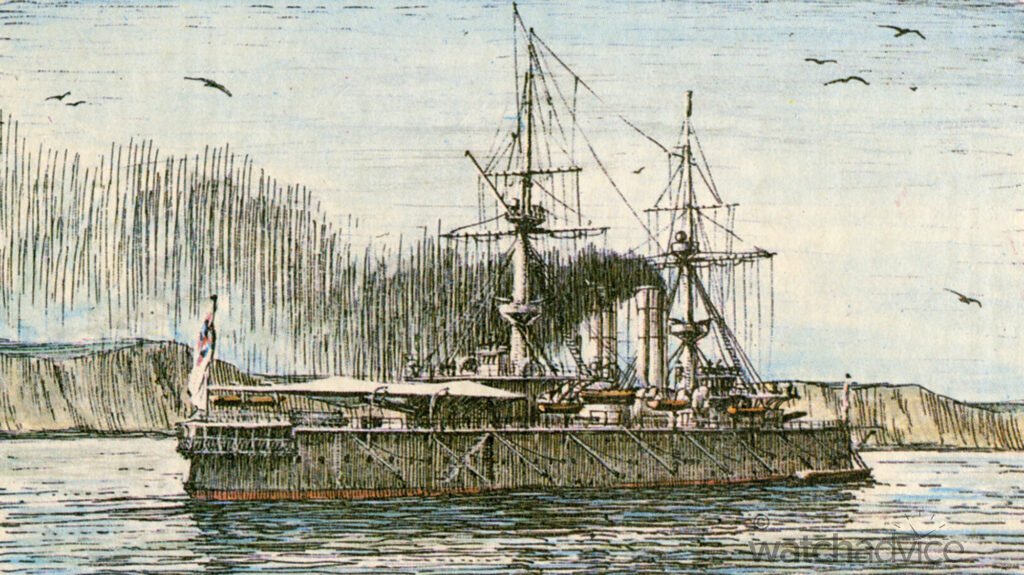

Audemars Piguet isn’t clear on where the name “Royal Oak” actually derived from. The brand states, however, that there were two possible scenarios. The first reference was almost 400 years before the birth of the watch when the Battle of Worcester in England took place in 1651. It is said that Charles II of England hid in a nearby “Oak Tree.” In another reference, it is said that the watch is named after the English Royal Oak battleships of 1892.

With the history lesson out of the way, let’s now dive deeper (pun intended!) into the design specifics of the different components that make up the legendary Royal Oak timepiece!

Designing The Royal Oak Case

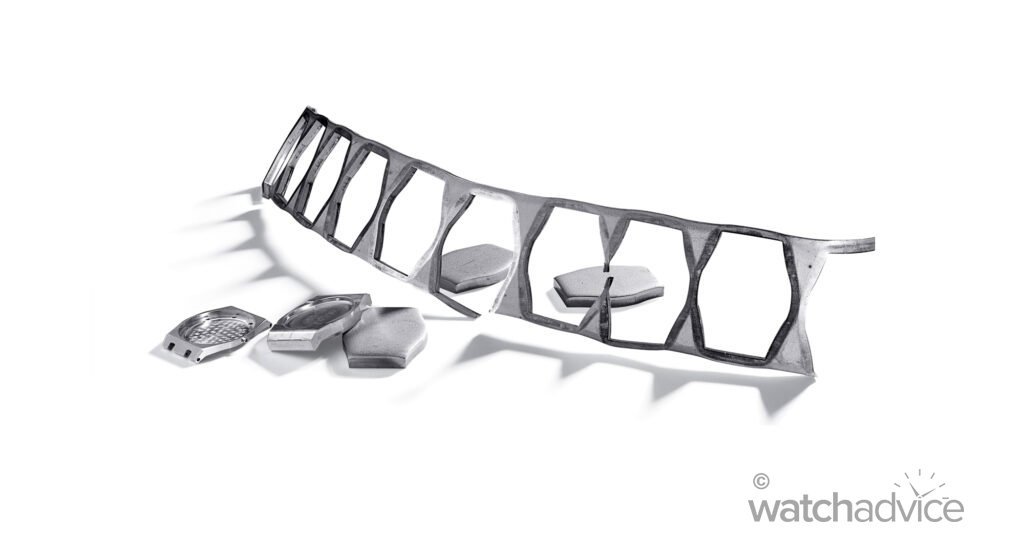

From a technical and aesthetic standpoint, the Royal Oak case can be seen as a masterpiece. It combines different geometric shapes by combining a rounded octagon, a circle (for the dial), and the more traditional tonneau shape case. The case of the first Royal Oak (ref. 5402) is described as a monocoque.

It should be noted that Audemars Piguet recently revealed from the archives that the first four prototypes of the Royal Oak case and bracelet weren’t actually made from steel. In fact, Audemars Piguet up until the release of the Royal Oak, was mainly working with gold (white/yellow) and platinum for their watches. Making a “sports model” in steel was an “anomaly”, as the brand states. The first four prototypes of the case construction (and bracelet) were made from white gold before the brand could move into creating it from steel.

Monocoque Case Construction

Albert Berner in 1961, in his book, the Illustrated Professional Dictionary of Horology, explains that “a watch case has two functions. The first is to protect the precious and fragile mechanical watch movement against dust, damp and shocks. The second is to “give the watch as attractive an appearance as possible, subject to fashion and the taste of the public.” He then further explains that a watch is usually composed of three segments superimposed on each other (see the above picture). These three elements are usually the bezel, case middle and case back. This construction can still be found in many modern timepieces today.

The monocoque case, however, takes a simpler approach by only having a two-piece construction. In this design, the “bezel” and “case middle” are done as one piece, with the case back still being an individual component. Therefore, when the monocoque case is constructed, the structure reduces the risk of moisture penetration, making the case more rigid and sometimes allowing it to be slimmed down while maintaining access to the movement through the back of the watch.

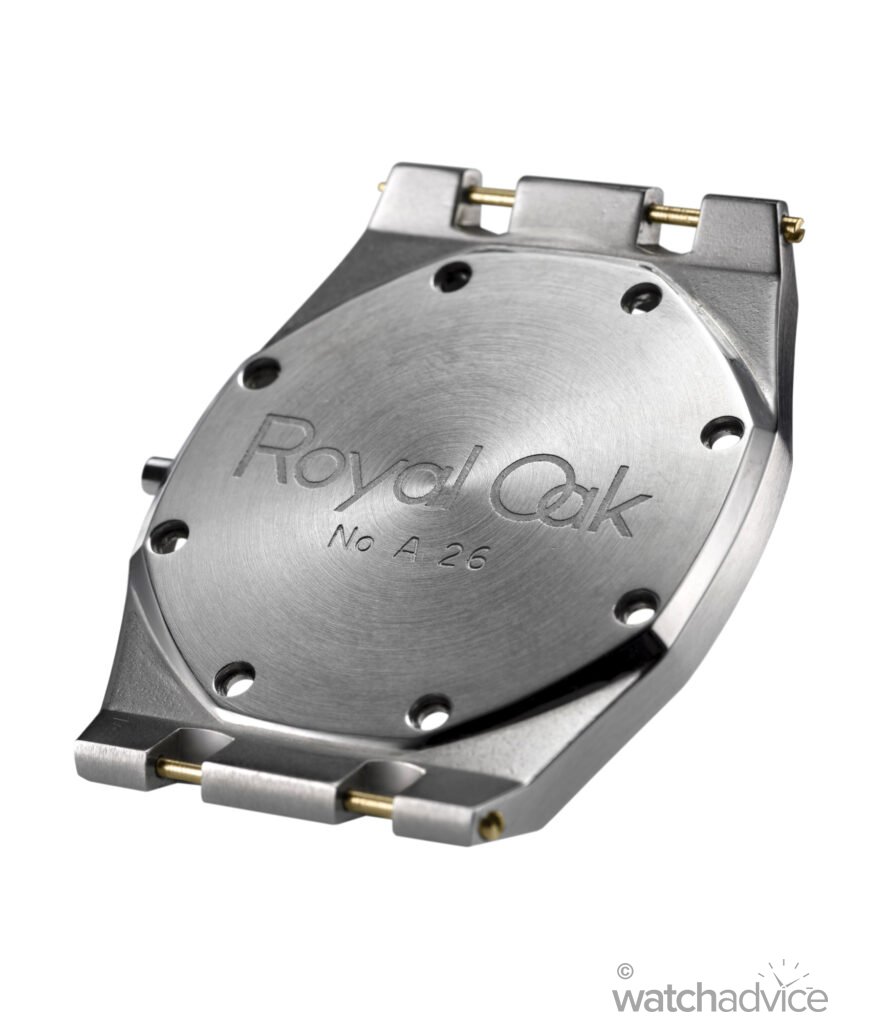

The Royal Oak ref. 5402, however, took the opposite approach. The timepiece’s middle case and case back were fused together, with only the bezel needing to be superimposed on top. To put it simply, the top component, which features the eight-sided bezel and lugs, will be connected to the middle case and caseback (both of which are now a single component) through the hexagonal screws. As the screws are embedded into the bezel, they will initially be placed on the bezel and then tightened on the caseback.

Case Middle and Caseback Construction

As mentioned above, Royal Oak’s monocoque case construction merges the case middle and caseback into one component. This component is carved from one single block of steel. When looking from the front, the component has a tonneau shape with a circle for the dial. However, from the back, the circle shape disappears to make way for a rounded octagon, which echoes the shape of the bezel placed on the front. This gives a completely balanced look from top to bottom. The case middle part of the component is slightly curved so that it matches the contours of the wrist more closely, providing a better and more comfortable fit on the wrist.

For the more modern Royal Oak 15202, an article published in 2012 celebrating the Royal Oak’s 40th anniversary explained the process in which the case was constructed: “This means that after the initial blanking operations, the 44 successive turning, milling, trimming and engraving operations must be isolated. All contribute to preparing the monohull case for manual polishing. When the surfaces are pierced in order to house the case and movement fastening screws, and the inscriptions are engraved, it’s time to apply the finishing. The case, sides and lugs are satin-brushed along different axes and in several stages.”

Royal Oak’s Iconic Octagonal Bezel

What made the Royal Oak so unique at the time of its introduction was the use of different geometric shapes in its construction. The now iconic octagonal bezel had a lot to do with that. The Royal Oak’s bezel is often seen as purely an octagonal shape, but it’s far more than that. The centre shape is a circle (as can be seen from the image above), while the outer edge shape of the bezel is a rounded octagon, making this seemingly simple element quite complex.

The 40-degree bezel perfectly follows the contours of the bezel’s octagonal shape. This bevelled surface then undergoes a mirror-polished finish, which completes the stunning look of the bezel. Not only that but when looked at from the front, it connects the moiré reflections of the Tapisserie dial to the facets of the tapered integrated bracelet.

The Signature Hexagonal Screws

One of the most disruptive design elements upon the Royal Oak’s first release in 1970 was the eight hexagonal screws punctuating the octagonal bezel. It is said that the advertisers of the Royal Oak used this non-conformity to traditional watch design standards as a way to poke fun at its difference by saying, “A price like that, he teased, and they don’t conceal the screws?”

Gerald Genta’s use of the hexagonal screws is ingenious, to say the least. While the slots of the screw heads seem like they can be turned with a screwdriver, it is, in fact, the complete opposite. Once placed onto the bezel, the hexagonal screws are firmly fixed in place, meaning the screws are not able to turn at all. So, how does the design allow for the tightening of the monocoque case?

The secret to this clever design lies in the fact that the hexagonal screws are fitted with round nuts introduced from the back of the watch, which act to close the case construction and tighten it. However, due to the nature of this design, the screws were susceptible to corrosion, especially as they were made of steel. This made removing the screws for movement inspection incredibly difficult, which prompted Audemars Piguet to create special drill bits and a whole set of tools to drill these screws. Due to these circumstances, this led to the brand to create the Royal Oak hexagonal screws in white gold.

Design of the Dial – Petite Tapisserie Decorative Pattern

The dial of the Royal Oak features the Petite Tapisserie decorative pattern. This design has been part of the Royal Oak’s core design element since its creation in 1972 and is still used today in modern Audemars Piguet Royal Oak models. The Petite Tapisserie decorative pattern consists of hundreds of small truncated pyramids set on a base dotted with tens of thousands of tiny diamond shapes.

The conception of the Petite Tapisserie decorative pattern started in 1970. Audemars Piguet recalls the story as “a Geneva-based company called La Nationale lost its only employee capable of operating seven old machines that were about to fall into disuse. These engraving machines, or more precisely “guilloché copying” machines, had been used for decades to reproduce geometric or floral tapisserie patterns on gold lighters, pens or cigarette boxes in silver, gold, etc. Wishing to dispose of these tools, La Nationale handed them over to its neighbour, the dial-maker Stern Frères, on condition that they fulfil an existing order. Stern was nothing less than the most prestigious dial manufacturer of the 20th century. It supplied the greatest watch brands, including Patek Phillippe (which the Stern family bought in 1932), Vacheron Constantin and Audemars Piguet.”

Construction of the Petite Tapisserie Pattern

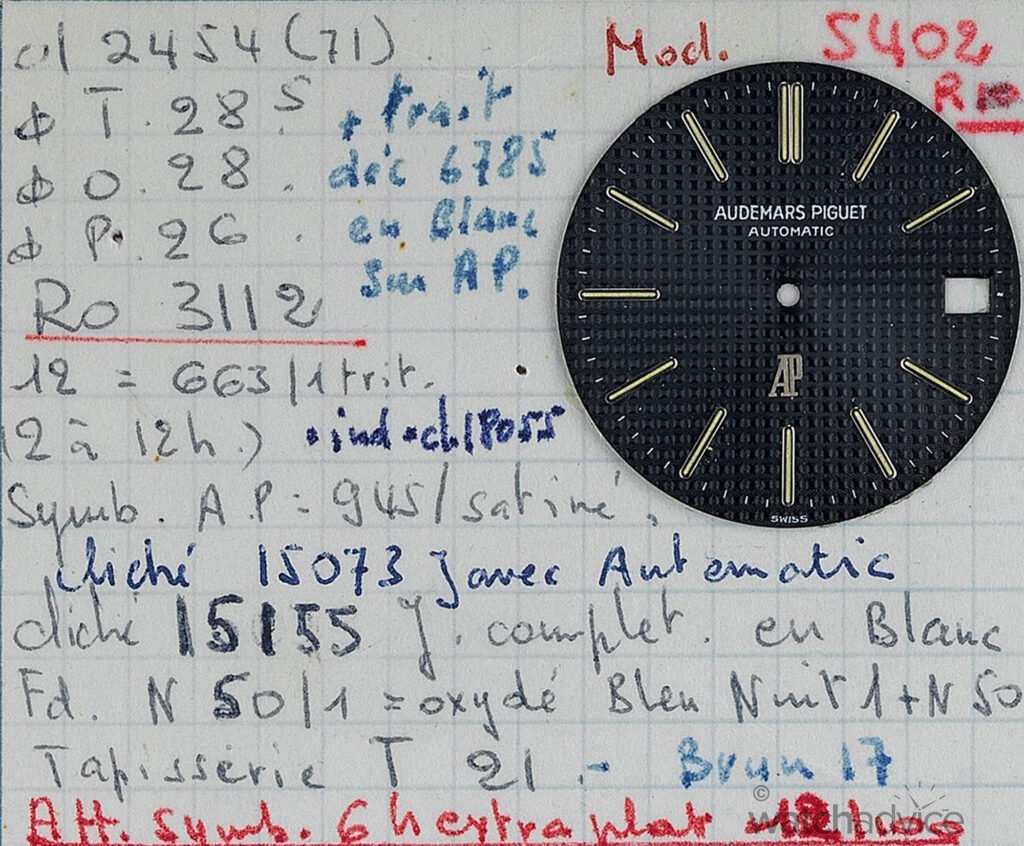

Gérald Genta visited Stern Frères to discuss the Royal Oak concept and its future. During this discussion, 300 templates, each with a different design, were shown for the possible dial design of the Royal Oak. Gérald Genta and Stern Frères chose 13 designs to make prototypes, including one called T21, standing for “Tapisserie 21.” This would be the design of the Royal Oak dial, now renamed to Petite Tapisserie.

The Clous de Paris guilloché pattern loosely inspires this T21 or Tapisserie 21 pattern. Its origins can be traced back to the 18th century, and its design, similar to the Tapisserie 21 pattern, consists of small pyramids with square bases. The Tapisserie 21 pattern consists of hundreds of small, flattened pyramids aligned in a checkerboard pattern, crisscrossed by the same number of horizontal and vertical lines, mimicking the imagery of a city’s streets.

Just like the Royal Oak’s case, which has been designed to play beautifully with light, the dial has been constructed with the same intentions. The subtle combination of geometric shapes features several patterns that have been superimposed to ultimately create varied moiré effects that reflect light elegantly.

“Bleu Nuit 1 + N50” Dial Colour

Unlike the Petite Tapisserie dial pattern, the colour of the dial had already been decided by Gérald Genta. After the dial pattern was chosen, colouring this to Gérald Genta’s specific colour choice presented a major technical challenge. The colour must neither detract from its innumerable tiny details nor excessively dim the light effects. Painting the dial was certainly out of the question, as this would cause the tiny diamond-shaped holes to get blocked, thus eliminating the Petite Tapisserie dial’s stunning lighting reflections. The dial colouring choice was to use the electroplating technique, which involves applying an extremely thin layer of colour to the dial.

Audemars Piguet states that from Stern’s archives, “the dial of Royal Oak Ref. 5402 is described as “Bleu Nuit 1 + N50”. The Bleu Nuit, no 1 colour, was created by Stern, who had jealously guarded its trade secret. The N50 indication meant Nuage 50 (cloud 50), the cloud being produced by the small amount of black colour poured into the liquid lacquer before it was applied to the blue dial.”

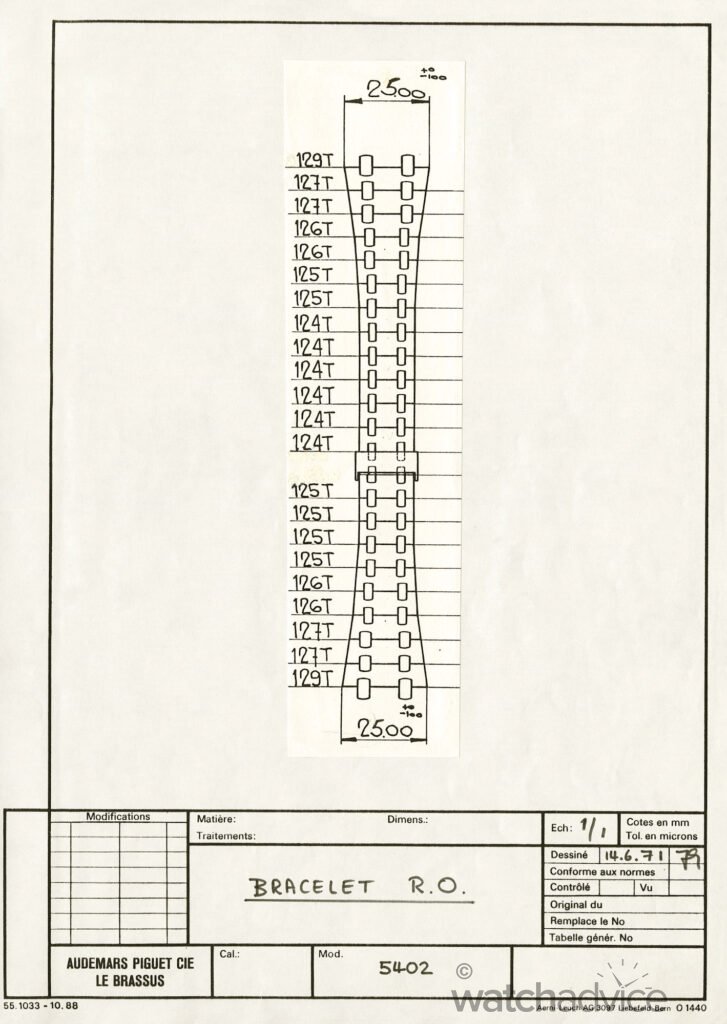

Design Of The Royal Oak Bracelet

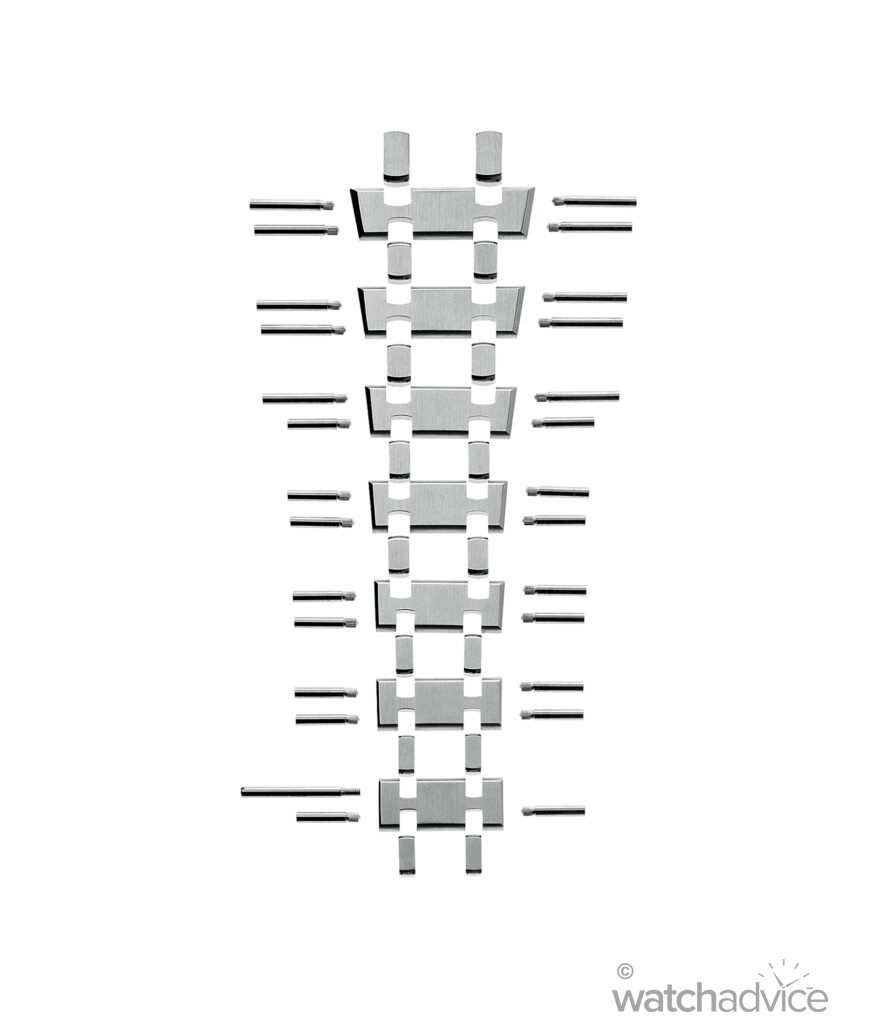

Gérald Genta’s integrated bracelet design for the Royal Oak was far from the first integrated bracelet in the watch market. However, it was one of the most complex bracelets made from steel at the time. Genta’s Royal Oak bracelet featured 154 components, among which 34 were of different sizes. The aim of creating this bracelet was to manufacture the first-ever sports bracelet with a flair of artistic craftsmanship.

In 2011’s Gérald Genta interview, the designer stated the importance of the Royal Oak bracelet as “Seeing just a few centimetres or even a few millimetres is enough to get the picture and you don’t need to see everything, which confirms how important it is!” He added that as far as the Royal Oak was concerned “The whole point was to make a steel selfwinding watch equipped with an expensive movement. The bracelet had to be extremely flat, thin, supple and aesthetically pleasing, playing with light thanks to the flat satin finish. When you see the watch on your wrist, the light sings on the bracelet!”

To make Genta’s Royal Oak bracelet design concept into reality, Audemars Piguet went to one of the greatest bracelet design specialists of the time: Gay Frères. We’ve all heard and know about the work the Geneva-based company has done for various brands in the watch industry, such as creating the Oyster bracelet for Rolex, the Rice grain bracelet for Patek Philippe, and bracelet designs for Chopard and Zenith, just name a few. Gay Frères was an undisputed master in making steel bracelets, so it was the obvious choice for Audemars Piguet and the Royal Oak bracelet design.

However, even with the vast experience and tools at their disposal, the artisans at Gay Frères weren’t able to attain the level of finishing that Audemars Piguet was asking for. This meant that each bracelet that was produced, had to be re-worked manually by hand by the Le Brassus watchmakers. After the launch of the Royal Oak in 1972, Audemars Piguet made several improvements to the bracelet’s design so that the expected degree of quality and finish can be met consistently. Aside from Gay Frères, several other companies also took on the ambitious task of developing the Royal Oak bracelet, such as Fontana, Lascor, GTF and Centror, which is currently the Audemars Piguet Meyrin subsidiary.

In the modern day, the Royal Oak is known for many different features (as outlined above!), with one of them being the beautiful glistening of the bracelet. While the integrated bracelet with its tapered links is a stunning design in its own right, the shine of the bracelet is what gets everyone talking, and rightly so. It’s safe to say that Gérald Genta achieved his vision of having the bracelet be “esthetically pleasing, as when you see the watch on your wrist, the light sings on the bracelet!”

Audemars Piguet states that this finish is acquired through surfaces of the bracelet being “finely satin-finished, with the same grain as those of the case middle and bezel, so as to reflect the light smoothly and create an effect of continuity that reinforces the impression of an “integrated bracelet”. The lateral edges are bevelled and worked on with a lapping machine or grinding wheel in such a way that the light bounces off them as brightly as the movement’s bevelled steel parts!”

The Legacy Of Royal Oak Watch Design

As we look back on the legacy of Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak watch design, we can clearly see that its journey from a revolutionary concept (thought overnight!) to now a watchmaking icon showcases the essence of what is really horological innovation and timeless elegance. When the Royal Oak was first introduced in 1972, it marked a shift in the luxury watch industry, and not just for one design element of the watch, but for many different aspects that were truly unique at the time, to creating what we see now as a masterpiece.

Not just that, but appreciation must be given to Goerges Golay and Gérald Genta for having the audacity to set a new standard for luxury mechanical timepieces while also redefining what a high-end timepiece could be by challenging conventional norms with its bold design, all during a time when mechanical watchmaking was going through its worst period in history with the Quartz crisis.

Thanks to the bravery of these gentlemen, who pushed forward during difficult times, we now get to enjoy an iconic timepiece that captivates watch enthusiasts and collectors alike around the world. As we look toward the future, Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak stands as a testament to the power of visionary design and the timeless elegance of exceptional mechanical watchmaking.

Tune in for Part 2 of Legacy Of Iconic Watch Designs: Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, where we look at how the Royal Oak has evolved over the years, including the many different complications it now holds!