In this education article, we dive into the history of the tourbillon, how it works, and the brands at the forefront of horology’s most iconic innovation.

Exquisite, Exclusive, and Expensive: These are three words commonly associated with the appearance of a tourbillon in a wristwatch. It’s a thing of beauty, often showcased as the beating heart of our little machine companion, and represents one of the highest levels that watchmaking can go to.

If you’re familiar with the watch world, everybody knows exactly what it is, but not everybody knows why it’s here and what it’s used for. Who invented the first one? When did they end up in wristwatches? And is the modern-day tourbillon completely redundant? Read on, and find out!

History of the Tourbillon

In French, tourbillon means ‘whirlwind,’ denoting the complication’s rotating cage and oscillating balance wheel. It’s a hypnotic dance of mechanics that suits its French name exceptionally well.

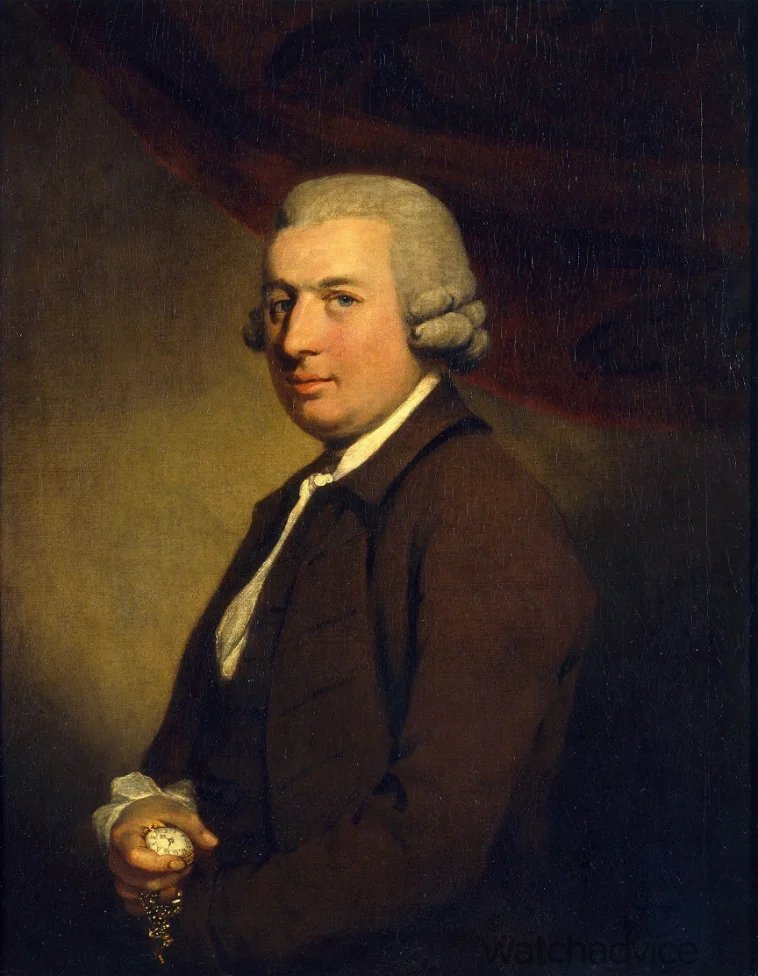

A more obvious reason for the French namesake is its patenting inventor: a Swiss-French watchmaker named Abraham-Louis Breguet, whose name lives on through the Breguet brand. While he is commonly solely credited for the tourbillon, another equally legendary watchmaker was responsible for its conception.

John Arnold, a British watchmaker and inventor from Cornwall, enjoyed a close working relationship with Breguet, honing each other’s skills until he died in 1799. Dismayed yet undeterred, Breguet would eventually finish what they both started. In 1808, he produced the world’s first functioning tourbillon movement, encased in an Arnold pocket chronometer symbolising their friendship. Though Arnold’s life and legacy similarly live on through the Arnold & Son brand, the tourbillon remains closely associated with Breguet. In his lifetime, he would go on to create 35 more tourbillons, of which only about 10 exist today.

During Breguet’s time, tourbillons were primarily used as a functional tool, but in the 1860s they had become commonplace outside of Breguet’s works. This meant that the tourbillon had to evolve to survive, which it did thanks to the work of Constant Girard. He, alongside his wife Marie Perregeaux and her family, would go on to create the Girard-Perregeaux La Esmerelda, or the Tourbillon with Three Golden Bridges. This would mark a major turning point in the watch industry, where form met function, and set the precedent for the tourbillon’s transition from innovative to iconic.

Once again, though, it had to evolve – the turn of the 20th Century and the aftermath of World War 1 made wrist-mounted watches more popular than ever, and soon the market was scrambling to make the world’s first wristwatch tourbillon. This is an area of horological history that is somewhat murky, as two brands could potentially lay claim to this discovery: the French brand LIP and Swiss powerhouse Omega. While LIP was making tourbillon prototypes throughout the 1930s, it seems that Omega beat them to a functional one with the Cal. 30 I tourbillon in 1947. It’s an incredibly under-the-radar tidbit of information I was not aware of until I read about it for this article, and adds an incredible feather in the cap of Omega’s already fascinating heritage.

Today, the tourbillon’s newfound reputation and its incredibly rich heritage are mostly associated with haute horlogerie, the highest expression of horology. Of course, the Breguet brand has carried on the legacy of its esteemed founder, as has Arnold & Son. However, almost every watch brand has jumped on the tourbillon train, creating tourbillons for a wide array of price points (and build qualities). Still, no matter who’s making them today – whether it’s Patek Philippe, Bulgari, Horage, or even Sugess – the tourbillon’s reputation can never be muddied, and represents one of watchmaking’s greatest achievements.

How Does It Work?

The average mechanical watch’s accuracy depends on several factors, such as temperature, beat rate, and general build quality. However, there is one factor above all that is a major determinant in the accuracy of your watch: gravity.

In the era of pocket watches, Arnold and Breguet set out to solve this seemingly inevitable problem. As your pocket watch was in your… uh, pocket the entire time, gravity would take effect on the regulating organs of your watch. The balance wheel, escapement, and hairspring would be gradually pulled downwards by gravity, throwing the watch’s accuracy out of whack.

Thus, the tourbillon is a cage that rotates those regulating organs, ensuring that gravitational tension is dispersed equally. Think of it like a Ferris wheel – As it rotates, each cabin momentarily feels gravity’s pull as it gets closer to the ground. Without a tourbillon, the Ferris wheel is stopped and the cabin closest to the ground gets unbalanced over time, constantly experiencing the most gravitational pull.

Continually changing the orientation of the regulating organs over time means that the watch maintains a high level of accuracy throughout its lifespan. With its rotating cage, it’s not a wonder why most watch brands ensure they make the tourbillon the main attraction of the dial, typically cutting out a section for it to sit. If you’re like Roger Dubuis, you’ll want to make it the only attraction, as their latest Orbis In Machina centrally-mounted tourbillon demonstrates.

But nothing good ever lasts forever, and in the modern day, the tourbillon’s practical implications have diminished due to the advancements in technology. However, the functional usage may have been lost as soon as it transitioned into wristwatches. Tourbillons were built to counteract the pocket watch’s positional problems, but since a wristwatch is mounted on your hand it isn’t similarly as vulnerable to such an issue. I believe the ‘practical’ tourbillon watch was killed when watch brands began to adjust their movements to all positions. But what does that mean?

At some point, you’ve probably encountered a watch with text engraved on the movement, which states something along the lines of “Adjusted to [insert number] Positions.” This is indicative of how the watch will fare in six different positional scenarios:

- Horizontal, Dial Up (DU)

- Horizontal, Dial Down (DD)

- Vertical, Crown Up (CU)

- Vertical, Crown Down (CD)

- Vertical, Crown Left (CL)

- Vertical, Crown Right (CR)

If a watch is adjusted to all positions like the above Laurent Ferrier, it implies that its accuracy is maintained no matter how you leave it. Of course, some positions are more necessary than others. Let’s be real, unless you’re taking Instagram shots of your watch, you’re not keeping it at CR – nor would any sane human being sit their timepiece upside-down (CL).

However, it infers that the brand and its watchmakers took a lot of time to tailor-make and adjust that watch, making it more desirable for you, the consumer!

If your watch is that finely adjusted, then what exactly is the point of a tourbillon anymore? This question has been in the thoughts of many, but there is an answer. As mentioned earlier, the tourbillon has this legendary status, serving as a shining example of the pinnacle of watchmaking artistry. Even after centuries, it remains one of the most challenging complications to craft. It’s a showcase of our mastery over the intricacies of time. And let’s face it, they just look damn good.

Tourbillons Today

The tourbillon’s design has had over two centuries to evolve and adapt to the ever-changing watch industry. As a result, the modern tourbillon is surprisingly versatile and has been presented in an innumerable amount of ways. However, there are four general types of tourbillons you will find in the watch industry:

Classic Tourbillon

A classic tourbillon is indicative of a traditional tourbillon design, following Breguet’s originals in both aesthetics and functionality. This consists of a cage containing the regulating organs and is supported from the bottom and the top, mounted to a bridge. It’s a fairly bog-standard design, but one that’s no less complicated – Kind of like how basic math and basic calculus require two entirely different skill levels.

The above Breguet Classique Complication 5317 is a great example of a classic tourbillon, where the cage is mounted to an upper bridge held together by two blued screws. Mechanically, classic tourbillons are also differentiated by their rotational speed, one revolution per minute. This is how it was for Breguet’s original tourbillon, which turned out to be pretty useful if you wanted to indicate the seconds. We at WatchAdvice are massive fans of Breguet, and we even think that they are almost criminally underrated. If you want to know more, you can check out our thoughts here.

Flying Tourbillon

The flying tourbillon is arguably the most popular form of tourbillon seen in modern watchmaking. This is because, unlike classic tourbillons, a flying tourbillon is supported from the underside only. While lacking in mechanical advantages over its classical counterpart, the flying tourbillon makes up for it in style: Doing away with the upper bridge allows for an unobstructed view of the tourbillon and its moving parts, enhancing it’s already mesmerising aesthetics. The flying tourbillon also appears separate from the rest of the dial, giving the impression that the tourbillon is floating on thin air.

It’s a contemporary complication that often features in avant-garde design, so the TAG Heuer Carrera Chronograph Glassbox Tourbillon is a perfect example of such. A modernised silhouette compared to the aforementioned Breguet Classique, this flying tourbillon model features a three-pointed cage, with a fourth protrusion indicating the seconds. They also recently released a teal version of this watch, which you can read about here.

Multi Tourbillon

Of course, the only thing better than one tourbillon is the presence of another. Thankfully, we have master watchmakers worldwide who are happy to take on this extremely ludicrous feat. A multi-tourbillon watch is exactly what it says it is: It uses more than one tourbillon. Not only does this make for an excellent novelty if you want to get either hypnotised or dizzy when you look at your watch, but it also serves a practical mechanical purpose. Adding extra tourbillons operating at different speeds and directions can all contribute to timekeeping accuracy, as they ensure your watch’s regulation is pinpoint regardless of its positioning relative to gravitational pull.

Probably the best example of the multi-tourbillon timepiece is perhaps the legendary Greubel Forsey Quadruple Tourbillon. Allowing for unimpeded access to the mechanics within, the stunning asymmetricality of this Greubel Forsey is undoubtedly one of the highest levels of watchmaking, if not the highest. Although this piece cost close to an eye-water AU$1 million during production, its existence is scarcely believable, showing just how serious watchmaking can get at its peak. Unless you were the Adelaide Powerball winner, however, you’re not going to be touching one of these any time soon.

Multi-Axis Tourbillon

Finally, this tourbillon variant is the one that makes the most sense to me, as it almost contradicts my argument that tourbillons as a complication are a mechanical irrelevancy. The multi-axis tourbillon is a tourbillon that doesn’t just rotate on a single axis. Instead, bi-axial and tri-axial tourbillons can rotate on two and three axes respectively, permitting for a wider coverage in counteracting gravitational pull on the regulating organs. Not only does this save space for more complications, but it also looks extremely cool – like a little mechanical planet that operates independently of the watch. Who needs ‘adjusted in all positions’ when you’ve got a watch that adjusts itself on the fly?

That question was deftly answered by Jaeger-LeCoultre’s grand release at Watches and Wonders 2024 – the Duometre Heliotourbillon Perpetual. With a completely uninterrupted view of this tourbillon’s magic, you can easily tell why this complication often lies within the extremely high end of luxury timepieces and shows just how far the tourbillon has come within its 200-year lifespan.

Advanced Tourbillon Mechanisms

Despite there being four basic types of tourbillons, there also exist ones that have been fitted with additional mechanisms that enhance their timekeeping capabilities. For example, the Grand Seiko Kodo ‘Daybreak’ entertains the addition of a Constant Force Mechanism to the tourbillon. Some tourbillons tend to slow down at the end of their power reserve, which the Constant Force Mechanism helps to prevent. Through its use, the tourbillon maintains the same energy and beat rate from beginning to end, permitting smoother operation and less time variance. Even all this barely scratches the surface of what there is to discover about this coveted complication. Remontoirs, Fusée-and-Chain mechanisms, differential gears – there’s still so much to be talked about when it comes to the constant innovations surrounding the tourbillon.

Final Thoughts

Still, the consensus is clear: The tourbillon’s heritage, engineering, and modern interpretations are the stuff of legend. It’s become abundantly clear that, despite its anachronistic nature, it doesn’t matter what people think of the tourbillon anymore. Like how vinyl is still a beloved part of music, or how people still use polaroids for photography, the tourbillon has cemented itself as a beloved form of horology and is yet another example of how sometimes the old ways are still the best – when you put a new spin on them, of course.