As we know, watch movements are some of the most complex and impressive mechanical machines around. The movement is filled with intricate mechanisms and parts that all work together harmoniously to drive the functions shown on the dial side. In this latest education article, we will be looking at one of the core pieces found in a mechanical timepiece: the Escapement.

If you’re not familiar with this part of the watch, it’s the heart of the watch that allows it to keep time accurately and beats away under the case. But, before we dive into how an escapement works and what a modern escapement looks like, it’s good to get an understanding of the history of the escapement and how it first came about.

The History of the watch escapement

The escapement’s invention in the world of horology is an important one. The escapement acts by distributing a small amount of energy from the mainspring. The mainspring is a part that is a large spring and is given power either by winding the crown or through the rotor that acts as the automatic winding system.

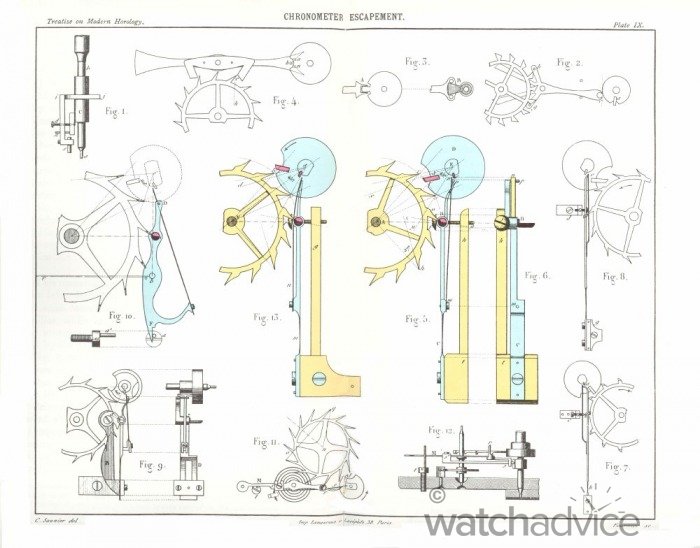

Over the centuries, the escapement has had many developments, from non-mechanical ones to escapement designs that never fully made it into modern designs. While there are certainly a lot of different escapement designs, the ones that stood the test of time are the designs that proved to be reliable and accurate. Outlined below are some of the different designs used for escapements, with the latter two being the modern designs used by watch manufacturers today.

Verge Escapement (13th Century)

The earliest known mechanical escapement is the verge escapement. Verge escapements were used from the early 13th century to roughly the late 19th century, mainly in pocket watches and clocks. The creation of the verge escapement was a vital one in the progress of mechanical clocks. The verge escapement allowed the measuring of time to become a repetitive oscillating process (pendulum swings).

The verge escapement can be described as a frictional rest escapement, as the escape wheel is always in contact with the balance wheel as it oscillates. One of the reasons, however, that the verge escapement never made it into mechanical movements in timepieces is that the gear train had to be momentarily driven backward while the balance oscillated. This not only resulted in inefficiency in the system, but also an inaccuracy along with unnecessary wear and tear on the parts.

Duplex Escapement (18th Century)

Invented by Robert Hooke around 1700, the duplex watch escapement is another frictional rest escapement. The duplex escapement was difficult to make, however, the accuracy achieved was much higher than the predecessor escapement mechanisms. The duplex escapement was used in English pocket watches from 1790 to 1860, and was also used in a timepiece, the cheap American ‘everyman’s watch’ the Waterbury from 1880-1898.

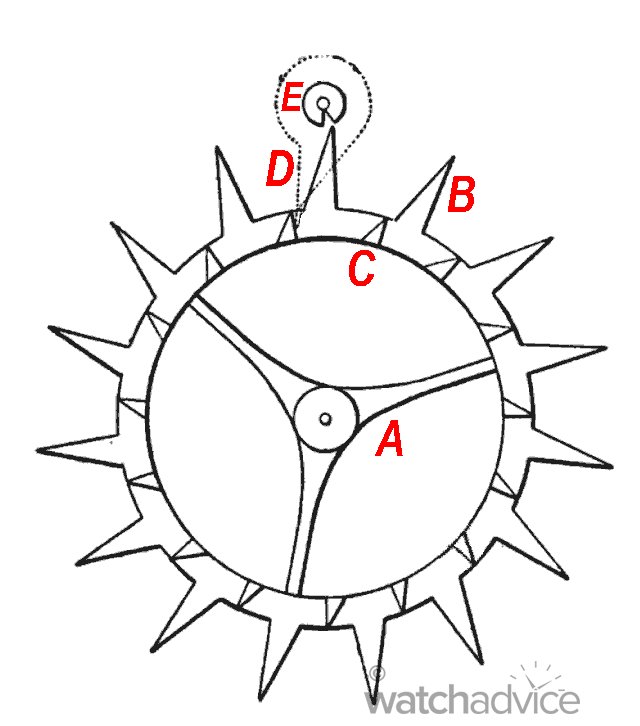

For the Duplex design, the escape wheel comes with two sets of teeth; long locking teeth that project from the side of the wheel, and short impulse teeth that stick up axially from the top. (Watch and clockmaking, Glasgow, David (1885)) states that “The cycle starts with a locking tooth resting against the ruby disk. As the balance wheel swings counterclockwise through its center position, the notch in the ruby disk releases the tooth. As the escape wheel turns, the pallet is in just the right position to receive a push from an impulse tooth. Then the next locking tooth drops onto the ruby roller and stays there while the balance wheel completes its cycle and swings back clockwise (CW), and the process repeats. During the CW swing, the impulse tooth falls momentarily into the ruby roller notch again, but isn’t released.“

The downsides to the duplex escapement were that, firstly, it was not self-starting, and if subject to shocks could abruptly stop the movement. Two things that are vital in mechanical wristwatches.

Lever Escapement (18th Century)

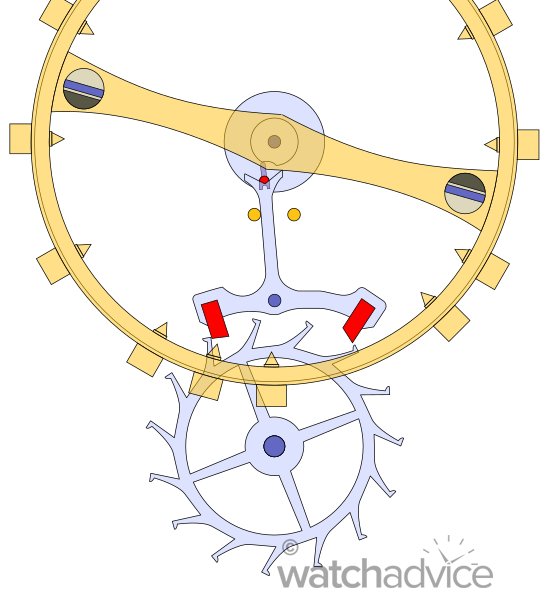

The lever escapement was invented by Thomas Mudge in 1750 and is the main escapement system used in wristwatches since the 19th century. This is also the modern escapement, used by many watch manufacturers around the world. So what makes this lever escapement highly desired by manufacturers?

Unlike the duplex and other previous escapement designs, the level escapement is a ‘detached’ escapement, where the balance wheel only comes into contact with the lever during the short period when it swings through its centre position, which, after it swings freely for the rest of the cycle.

The lever escapement is also self-starting, which means that if the watch/movement was to come under shock making the balance wheel stop, the escapement will automatically start again.

The lever escapement was modified by the British, Swiss, and also American watch manufacturers to suit their own timepiece movements. The original lever escapement was a ‘rack lever escapement’ which meant that the lever and the balance wheel were always in contact through a gear rack on the lever. The British took this design and created the ‘detached lever escapement’ which is where all the teeth from the gears were removed except one. The British design also had the lever at a right angle to the balance wheel.

The Swiss and American designs used the inline lever, where the lever is inline between the balance wheel and the escape wheel. This design is still what is used in most modern watches today.

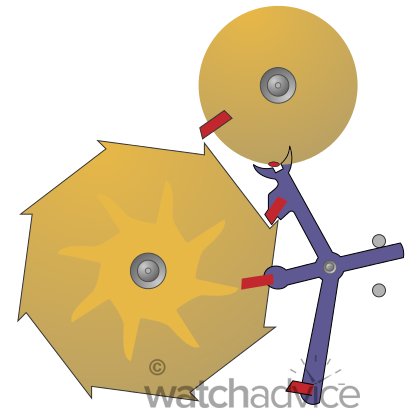

Coaxial Escapement (20th Century)

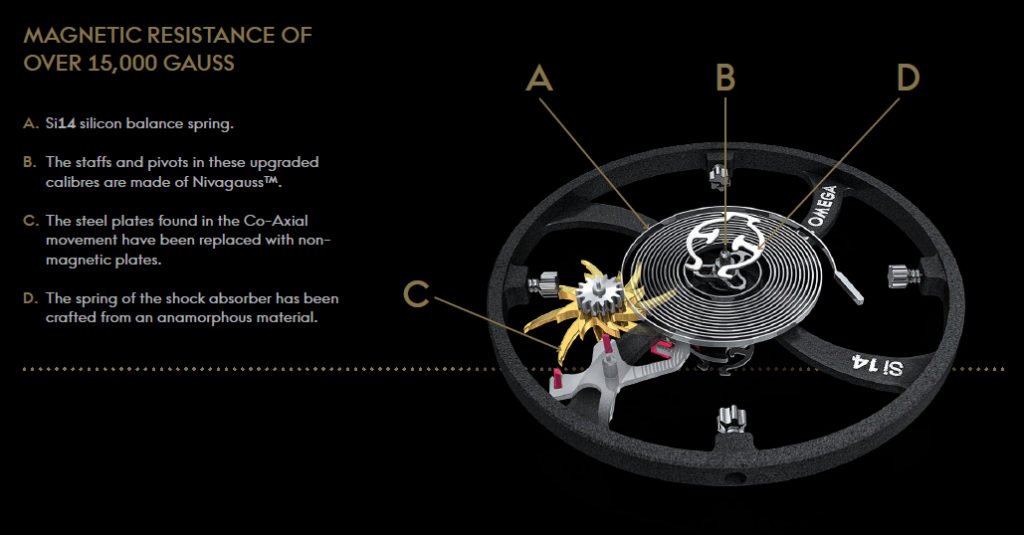

Created by British watchmaker George Daniels, the coaxial escapement was invented around 1974, with the mechanism being patented in 1980. Only a few decades old, the coaxial escapement is adopted by watch manufacturers even today. The coaxial escapement is a modified version of the lever escapement. The co-axial functions with a system of three pallets that separate the locking function from the impulse. And, instead of sliding friction, it uses radial friction at the impulse surfaces. Because this significantly reduces the sliding friction of the pallet stones over the teeth of the escape wheel, it eliminates the need to lubricate the pallets. The result is greater accuracy over time as well as a reduced need to have the watch serviced as frequently (CrownandCalibre).

Unfortunately, when George Daniels created the coaxial movement in 1974, the watch industry was going through the quartz crisis. In other words, mechanical timepieces were being pushed out, thus greatly reducing the need for specially designed escapements. Daniels didn’t let this phase him, however. Even though watch manufacturers weren’t interested in his design, Daniels took it upon himself to prove that his coaxial escapement would work. In 1975, Daniels created the coaxial escapement using his own components and then fitted it into his own Omega Speedmaster.

Even after presenting a working model, the brands were still reluctant to use this new escapement design. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that Omega themselves stepped in and decided to work with Daniels to help commercialize his coaxial escapement design.

In the modern watch today, only Omega and Roger Smith are using coaxial escapements in some of their movements. Both companies have used George Daniel’s design and have upgraded it to make it optimised for greater efficiency. Out of the two brands, Omega is the only brand using coaxial escapements on an industrial scale.

The Modern Day Timepiece

While there are certainly many different types of escapements used today, most of them form from the basic lever escapement design, with the brand’s then going further and improving them to suit their own movements. The escapement still serves the same function as it did centuries ago; a mechanism that converts rotational energy from the balance wheel into lateral impulses. The ticking sound that comes from most watches is actually from the escapement itself. At each rotation (or vibration) of the balance wheel, the pallet fork locks and unlocks with the escape wheel.

Without the use of an escapement in a mechanical watch movement, the watch would simply not be able to transfer energy in a way to power the watch and its many functions. Simply put, if the watch didn’t have an escapement and you were to wind it through the crown (or automatic rotor), it would unwind in a very fast manner, making the movement quite useless, hence proving just how important this mechanism is in the world of horology.

If this article sparked your interest in the movement of a watch, then check out our article where Matt tackled putting a gear train together in a manual wind watch at a workshop put on by Watches Of Switzerland and A. Lange & Söhne. There’s also an incredible time-lapse of the whole class at the end, be sure to check it out here.